Interview with Nathalie Bondil, Director and Chief Curator of the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts

/Nathalie Bondil, JP Gaultier, Thierry Maxime Loriot at the MMFA

by Ingrid Mida

For the past ten years, art historian Nathalie Bondil has been Chief Curator of the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, where she has curated many art exhibitions featuring the work of Picasso, Van Dongen and other artists. Ms. Bondil launched new programming by inviting fashion into the MMFA, with first ever retrospectives of the work of Yves Saint Laurent and Denis Gagnon. In 2007, Nathalie Bondil was appointed Director of the Museum. In 2008, she received the insignia of the Chevalier of the Order of Arts and Letters of the French Republic and on June 15, 2011, she received the title of Chevaliere of the Ordre National du Quebec.

Nathalie Bondil initiated the exhibition of The Fashion World of Jean Paul Gaultier: From the Sidewalk to the Catwalk which recently opened at the MMFA. The following is an excerpt of my interview with Ms. Bondil at the museum on June 13, 2011.

Ingrid: The MMFA seems to be the only museum in Canada to initiate and curate exhibitions of fashion designers. In 2008, you exhibited Yves Saint Laurent’s work and today, you are presenting Jean Paul Gaultier’s work. How is it that your mandate includes fashion?

Nathalie: We can do whatever we want to do and from my point of view that includes presenting the work of artists with a strong message. The fashions that Jean Paul Gaultier creates really says so much about the world, the society in which we live and I think that is very relevant for us. What Gaultier says about beauty and about taste is something that is very healthy, very relevant and very necessary.

Ingrid: I found it so refreshing this morning when Gaultier talked about beauty having no specific shape or look. Is that what attracted you to his work?

Nathalie: Completely. It is his humanist side and in fact, it is much more the sociological aspect of his work that I think is very important. It is so fresh as you say to say that everybody is welcome to wear his clothes: big, fat, old, whatever.

I think that it is our duty at the museum to open other doors. If you don’t have this critical look, if you don’t give people the tools to understand another way to consider the aesthetic of fashion, I think that you haven’t done your job.

This exhibition is not about branding, it is not about La Maison Jean Paul Gaultier. It is about Jean Paul Gaultier’s humanist vision of the society. And it is about very high values, about universal values beyond fashion.

What is interesting with him is that he is not just a fashion couturier, but he also collaborates with cinema, for theatre, for the avant garde, for the very popular rock stars. He is very curious and his mind is open and he has kept this child eye. He is always sincerely enchanted by people. I can say this is not a posture. It is not an attitude.

He is very humble. He has no flag, but in fact, when you consider his couture from the beginning until now, it is very coherent and consistent, and beyond humour, beyond provocation, there is also a very deep message.

Ingrid: Is that what defines JPG as an artist for you – that his pieces have a message?

Nathalie: Yes, absolutely. He has a very strong imagination that can reach us beyond fashion. You are not obliged to be a fashionista to be attracted to Gaultier because he has so many diverse interests in terms of multi-media and inspirations. He is not a stylist trapped within the discourse of fashion.

One proof is that he first said no to an exhibition. He did not want to make a kind of cemetery exhibition. He wanted to have an adventure, a new creation, to invent a new collaboration. This is what excites him, to make something different. He has so much imagination. He does not want to repeat himself. He does not have this narcissism towards the past. In fact, now he is still completely projected towards the future. And for him, this event is an installation, more a creation, something new.

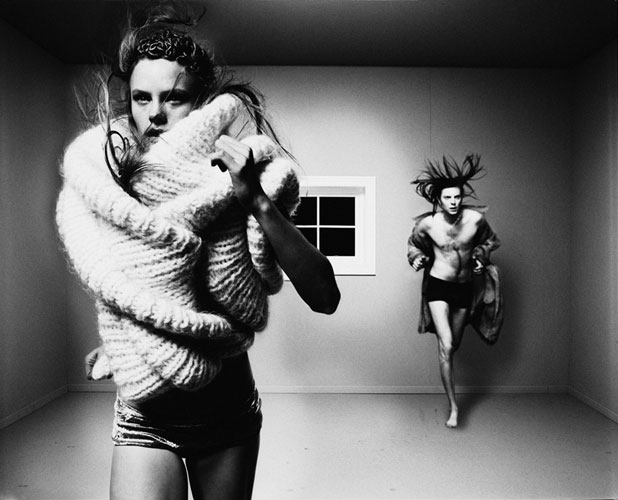

Jean Paul Gaultier Couture Collection (Courtesy of the MMFA)

Ingrid: I read that he once said “I don’t make works of art” and that “Fashion is not art”. Nevertheless, you have defined him as a contemporary artist.

Nathalie: He can have his own ideas. I have no problem with that. We worked with him as a contemporary artist. I told you he is always in the process of creation, never any repetition. And in my point of view, it is art.

It is art because haute couture has a sophistication of the milieu. As someone from outside, I was really, really impressed by the fact that all these couturiers have so much pressure. They must create on a very regular basis these new collections in a fierce competition atmosphere. At the same time they must also meet a commercial viability. There are no other artists who can support such pressure. It is so demanding in terms of excellence and so fascinating in terms of realization that I don’t understand why people say it is not art.

Ingrid: Is there a favourite part of the exhibition? Is there something that really resonates with you?

Nathalie: My favourite part of the exhibition is the man himself - Jean Paul Gaultier, the artist.

Ingrid: After I saw the McQueen show, I was wondering how you were going to live up to that standard, because it was quite unusual.

Nathalie: I very much admired what McQueen did. I did not see the exhibition yet and I will go next week. McQueen is very dark and Jean Paul Gaultier is like joy, optimism. They have very different sensibilities of what is a human being. One is like dark and one is like light.

For Gaultier, fashion is for real people. McQueen is not for real people. His work is fabulous - like sculpture, but you cannot live in it. There is a corset is in wood, but you cannot move in wood. And with that dress painted by spray guns projections, it is like the woman is attacked. Gaultier said he would have done it with real painters - like a dance, like an interaction with human people.

Ingrid: Some people say that McQueen’s work was misogynist, whereas it is the opposite for Jean Paul Gaultier. He seems to love women.

Nathalie: Completely. Yes, he loves not just women, but everyone.

Ingrid Mida is an artist, writer and researcher based in Toronto. She also lectures about the intersection of art and fashion.