By Sarah Scaturro

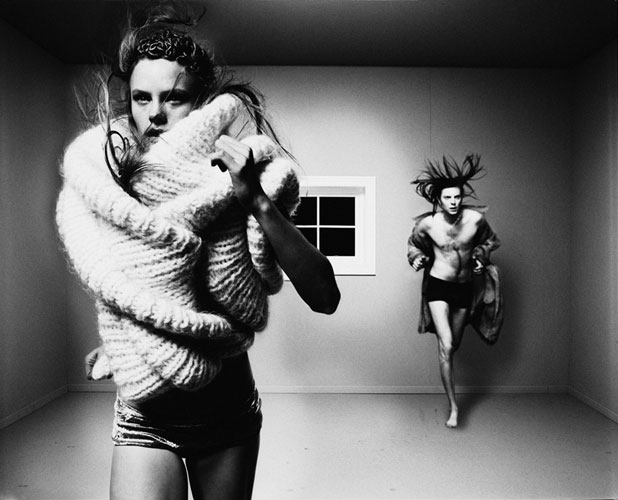

A favorite look from Titania Inglis' F/W 2012 collection. Photographer: Dan Lecca

Fashion Projects has been a fan of Titania Inglis ever since she launched her eponymous label a few years ago, so it was such great news to hear that she had won the 2012 Ecco Domani Fashion Foundation Award for Sustainable Design. While I initially thought of Inglis as an "eco" designer, it quickly became apparent that the term "eco" was simply too reductive for her design philosophy. For her, sustainability is not a gimmick, or just about sourcing yet another ecotextile. Rather, she is moving towards a concept of sustainability that emphasizes longevity, quality, and thoughtfulness. We are very pleased to present this interview with Inglis, coming on the heels of her recent F/W 2012 fashion presentation at Eyebeam.

Fashion Projects: Congratulations on your recent Ecco Domani Fashion Foundation Award for Sustainable Design. How has winning the award affected your business?

Titania Inglis: Thank you! Receiving the Ecco Domani award is such a dream come true — I didn’t believe it at first when I received the email telling me I’d won. It’s opened a lot of doors for me already within the fashion industry, and I was able to put together an incredible team for my show this season, including stylist Christian Stroble, makeup artist Lisa Aharon and hairstylist Ramona Eschbach, photographer Aliya Naumoff, set designer Ryan Crozier of Forgotten City — and collaborating on a series of leather body accessories with Bliss Lau, a designer whose innovative work I’ve admired for years.

Inglis making adjustments before her F/W 2012 presentation begins. Photographer: Georgina Southen

Your F/W 2012 collection presented a very cohesive vision, with a strong design vocabulary. Having followed your work ever since you began designing, I’ve noticed that you’ve developed signature elements. Your garments exhibit a strong affinity for geometry, asymmetry, and minimalism and you also create an unexpected sense of architectural space through your precise pattern-cutting and juxtaposition of rigid and supple fabrics. Can you explain a little bit about your inspirations, techniques and processes? Where did you hone your skills?

My father is an architect, so I grew up steeped in his lessons about architectural movements and polyhedra. As a math major in college, I was fascinated by topology, which studies surfaces and transformations — and I see fashion in much the same way: a transformation of two-dimensional fabric into three-dimensional forms, but forms that interact with the wearer’s body and personal style, and at the same time reference fashion history. Or to put it in less-nerdy terms, I find it magical to be able to go from a flat piece of fabric and a flat paper pattern, to an empty garment on a hanger, to a dress absolutely coming to life when its owner puts it on and imbues it with her personality.

I studied industrial design at California College of the Arts in San Francisco; conceptual design at Design Academy Eindhoven in the Netherlands; and fashion design at FIT. I learned my patternmaking skills from Prof. Evan Blackman, the outstanding menswear department head there, and through internships at Jean Yu and Threeasfour, both designers I loved for their ingenious and endlessly creative patternmaking.

One of Inglis' amazing coats from her F/W 2012 collection. Photographer: Dan Lecca

You continue to revisit designs, like your circle skirt, from previous seasons. Is there a reason for this? I personally think that by doing so you are reinforcing the well-designed, thoughtful process behind your clothing – they are so well-made, and “beyond” fashion that they don’t seem to go out of style.

I find that the most stylish women are those who sharply define their personal look and keep it over time, perhaps evolving gradually to stay current, but not changing constantly with the trends. I see my collection in the same light: adding interest from season to season in the form of new colors, patterns, and fabrications, while always retaining its underlying character. And part of that consistency lies in creating signature pieces that carry over from season to season.

Another advantage of bringing designs back is that it allows me the chance to refine them a little each season, as well as to experiment with different fabrications over time. I’ve discovered that my architectural silhouettes tend to work quite well in rigid as well as soft, drapey fabrics, and I love to discover them anew each time I source new fabrics.

Backstage at Titania Inglis' F/W 2012 presentation. Photographer: Aliya Naumoff

A look from Titania Inglis' F/W 2012 collection. Photographer: Aliya Naumoff

We often talk about the state of the eco-fashion movement in NYC. One minute we’re exhilarated about all the new things that are happening, and the next minute we bemoan the fact that it seems like such a small world, where everyone knows everyone and we’re all preaching to the same choir. Do you think the fact that you are considered an “eco” designer actually helps or hinders you? Do you ever feel marginalized or misunderstood due to having the “eco” tag attached to you?

To be honest, at this point, the word “eco” really makes me shudder. It’s been so overused that it’s come to represent a marketing gimmick rather than a serious philosophy of doing business, and I wish we could just retire it. I prefer to describe my work as thoughtful design, taking into consideration all the cradle-to-grave implications of each design decision, from the origins of the fabric I’m using to the future use and care of the garment. Ultimately, I believe that a beautifully designed and manufactured garment is the most sustainable thing to make: a piece striking enough to stand out in the here and now, yet classically proportioned and so well-made that its owner will want to wear it for a lifetime.

The most difficult challenge in designing sustainably is finding low-impact fabrics that are high quality and that fit with my clean, androgynous aesthetic. I’ve already traveled to London and Tokyo to source gorgeous organic fabrics, and scoured the New York garment district for dead stock options. And I’ve found some beautiful ones, but the more I search, the more I realize that the production process of the fabric is less important than beautiful craftsmanship and quality that will wear well over time. Taking the long view, production is only one part of the garment’s life cycle. If a fabric is made from organic wool, but pills and wears out almost instantly, then the fact that the farmer polluted less in raising the sheep is completely outweighed by the fact that the end product is quickly headed for the dumpster.

Another difficulty with sustainable design is people’s narrow interpretation of what that means. It’s not possible to design anything to be 100% perfectly sustainable; we all have to choose our battles. Some designers choose to use local production, others organic fabrics, others yet use zero-waste cutting techniques. I’ve had people question my use of leather; but as a lifelong meat eater, I’m happy that the skin from the animals we slaughter is used to make something beautiful. Leather exists mainly as a byproduct of the meat industry, and it’s a beautiful, supple, and long-lasting material that perfectly showcases my simple, architectural designs.

Set design for F/W 2012 presentation. Photographer: Georgina Southen

You've been collaborating quite a bit lately, with people like Bliss Lau and Christian Stroble, and organizations like the Textile Arts Center. Do you have any other dream collaborators you'd like to work with?

Working with Bliss and Christian this season was an absolute dream; in addition to having very strong fashion visions, they’re both incredibly smart and resourceful and really mentored me through the whole process of organizing a show and creating a larger collection. I’d never worked with a stylist before and was a bit hesitant to let somebody else impose their vision on my work, but Christian’s input really helped take the collection to the next level.

One of my favorite parts of running this line is collaborating with performers in other creative fields. My first season I choreographed a video with three Merce Cunningham dancers, and for last fall’s video I worked with a trapeze artist. Next up, I’d love to collaborate with a musician: There are so many dynamic, inspiring women in rock these days, from Alison Mosshart to Lykke Li to the Dum Dum Girls, and it’d be amazing to see them wearing my clothes!

What is next in store for you?

After all the excitement of the award and last week’s show, I’m taking it easy and waiting to see how sales go before I decide what to do next. Of course, taking it easy is relative; I’m also getting ready for sales, ramping up spring production, and in the back of my mind, starting to plan out the Spring 2013 collection and how I’d like to present it. I already have a couple of favorite new fabrics squirreled away that I’m dying to see made up in some nice architectural shapes. And I’d love to do a shoe collaboration next season...

Photographer: Georgina Southen

The first issue of the International Journal of Fashion Studies was recently published. Edited by Emanuela Mora (Università Cattolica di Milano), Agnès Rocamora

(London College of Fashion) and Paolo Volonté (Politecnico di Milano), it presents an innovative publishing model, by allowing articles to be submitted and peer-reviewed in a number of languages besides English. This approach acknowledges the scope and geographical breadth of the field and allows for a greater range of scholarship to be widely read, as the accepted articles are translated and published in English—which has become (for better or worse) the lingua franca of academia.

The first issue of the International Journal of Fashion Studies was recently published. Edited by Emanuela Mora (Università Cattolica di Milano), Agnès Rocamora

(London College of Fashion) and Paolo Volonté (Politecnico di Milano), it presents an innovative publishing model, by allowing articles to be submitted and peer-reviewed in a number of languages besides English. This approach acknowledges the scope and geographical breadth of the field and allows for a greater range of scholarship to be widely read, as the accepted articles are translated and published in English—which has become (for better or worse) the lingua franca of academia.