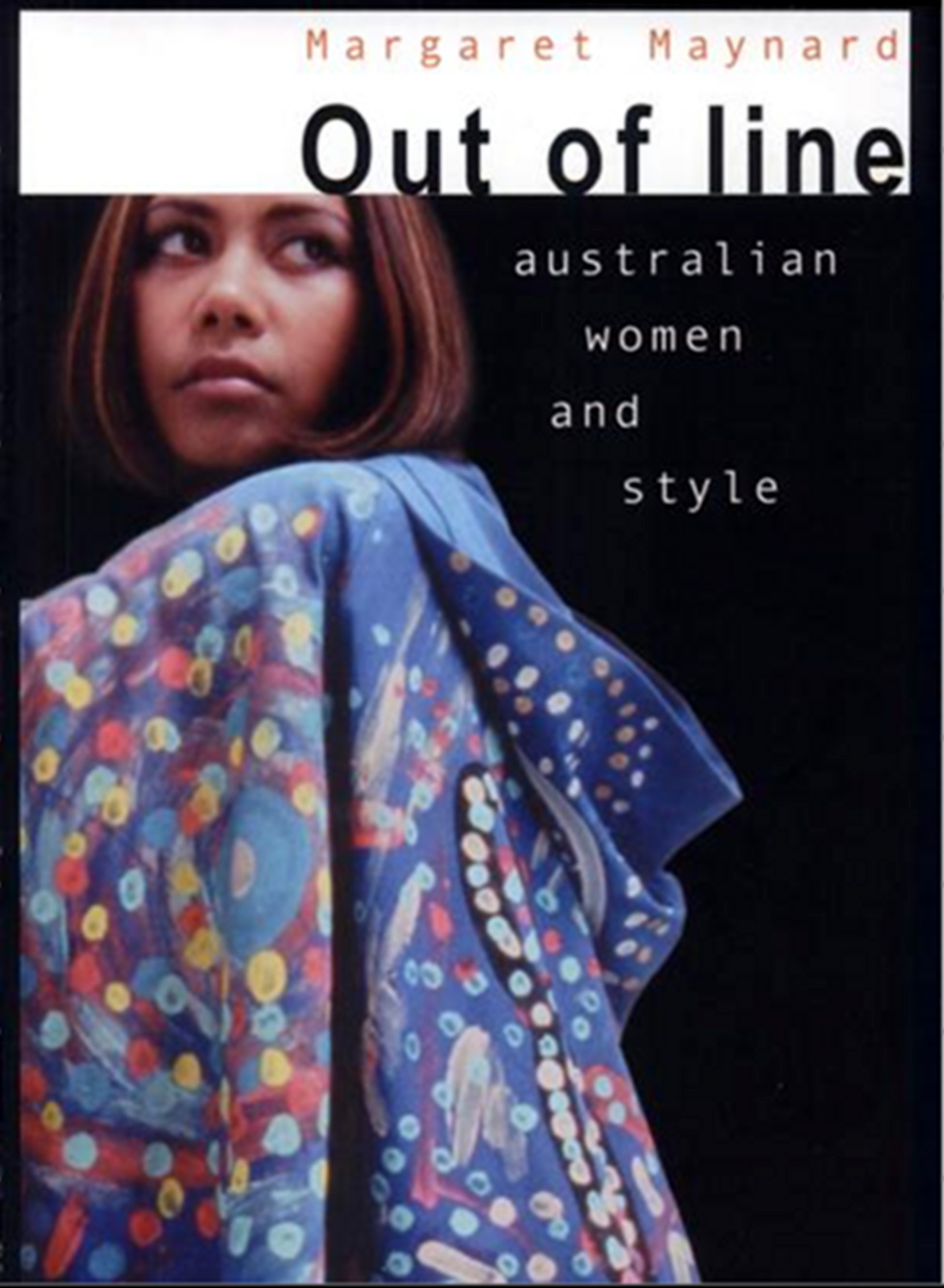

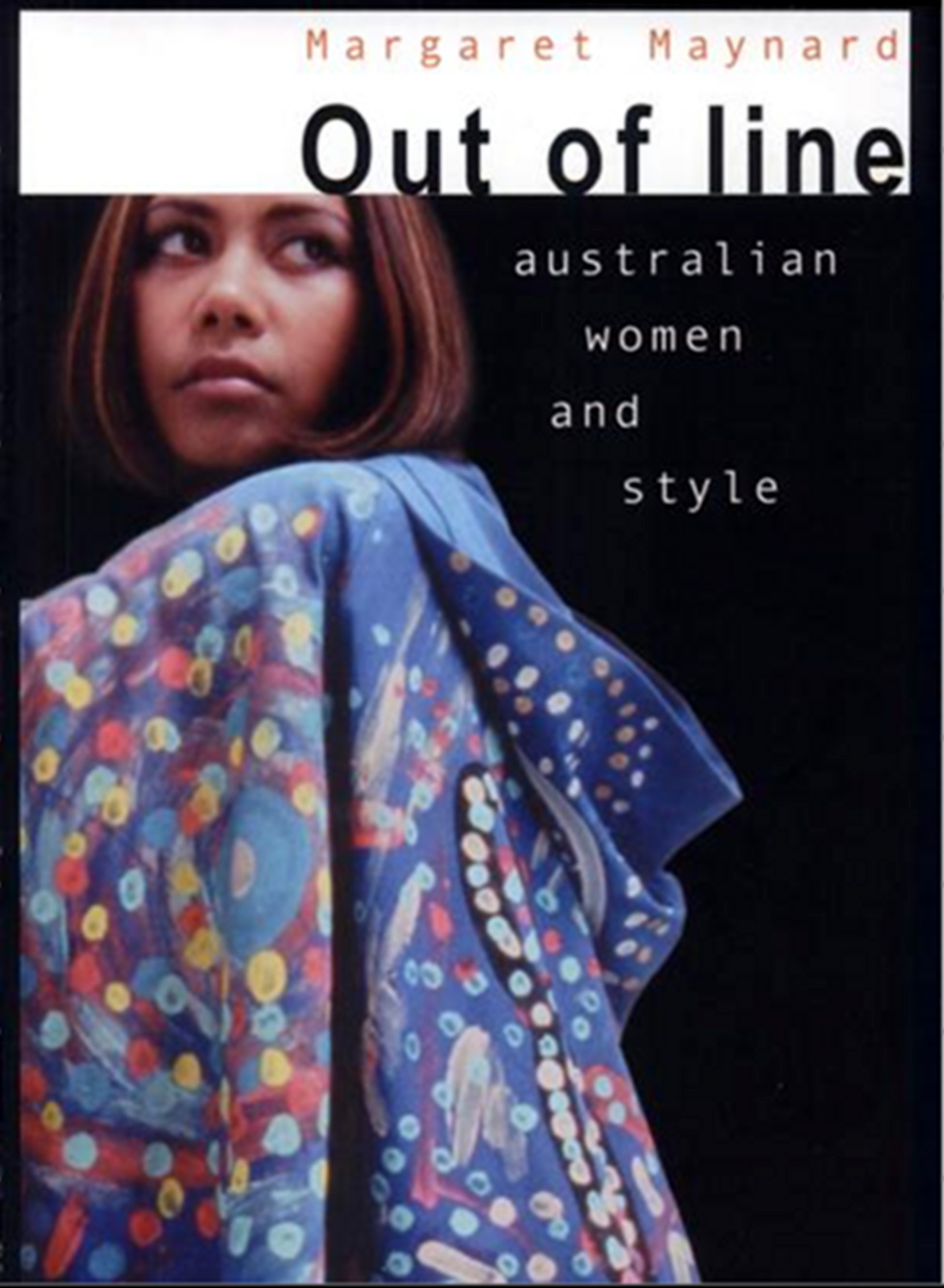

by Nadia Buick Cover of Margaret Maynard's Out of Line: Australian Women and Style.

Cover of Margaret Maynard's Out of Line: Australian Women and Style.

Associate Professor Margaret Maynard is one of Australia’s most respected dress historians. She has published widely in the field and taught for decades at The University of Queensland (UQ) at a time when dress and fashion subjects were few and far between. She continues to hold an Honorary Research Consultant position at UQ in the School of English, Media Studies and Art History. Maynard has contributed greatly to publishing on Australian dress and fashion. Her book Fashioned from Penury re-evaluated Colonial dress in Australia, debunked previously persuasive myths about the impact of the British Empire, class and gender while arguing for institutional acquisition of everyday clothing rather than ‘high fashion.’ In Dress and Globalisation she was one of the first to discuss clothing and sustainability and cross-cultural dressing practices. She also edited the Australia, New Zealand and the Pacific Islands volume of the Berg Encyclopaedia of World Dress and Fashion.

Margaret Maynard and I are both based in Brisbane (arguably quite far removed from the ‘centres’ of fashion) and I have been fortunate to work with her on a project about fashion in Queensland called The Fashion Archives. We spend a lot of time chatting via email and I recently took the time to ask her these questions…

You are a dress historian whose work has also occasionally examined fashion. What is your working definition for these terms?

Fashion for me is the highly volatile aspect of attire and behaviour—the latest look and comportment at any one time. It is a transformative concept or social ideal (not necessarily just reflective). Shaping and reshaping the body, it is an active and material demonstration of change, the nature of its visibility inextricable from social and cultural experiences. The other point is that fashion is inseparable from the industry in which it is made and more recently the commercialisation of its marketing and promotion.

For me fashion is a form of dress, so the term dress encompasses all attire, irrespective of economic factors or class. My view is that one can’t fully understand the workings and nature of fashion unless one takes into account wider processes of dressing. In fashion photography, for instance, one should bear in mind technical processes and the whole marketing structure of the industry. It has been said that fashion is where ‘costume’ and ‘dress’ converge but I don’t think that fashion should be thought of in this way. There are also degrees of fashionability dependent on class and economic circumstances as well as aspirations to look stylish.

Is ‘dress studies’ no longer fashionable?

Yes, I agree that ‘dress studies’ has the lower rating at the present time. Fashion studies today have cachet largely because they have become almost professionalised by the academy and the obsession with dense kinds of theory has lent to a sense of superiority amongst some practitioners. There are also convenient links to contemporary interests in design and lifestyle. And there is no doubt fashion benefits from its association with visual pleasure, aesthetics and artistic creativity.

Dress studies on the other hand seem intellectually less demanding and its subjects can give an impression of being mundane even drab. It is often downgraded as mere social or working-class history compared to fashion. It is interesting that second-hand dress rates more highly perhaps due to its association with self presentation as a creative form. The media loves fashion as allegedly newsworthy, with its links to the latest upmarket designs. Thus most newspapers have columns on ‘fashion’ where they seldom have on dress. The term ‘costume’ used to have the same low standing but somewhat upgraded now it has become the accepted term for theatrical performance attire.

Many theorists and critics interested in dress and/or fashion have observed the field’s relationship to women and femininity, and suggested that this close link is the reason that dress and fashion studies have often been overlooked. Have you also found this to be true? Do you think this is something that continues to happen?

I think that the association of dress/fashion with women’s interests was prevalent until the later 20th century. Historically fashion has been associated with vanity and folly, thus contributing to the perception it is not a serious study. The topic has been disparaged, written about defensively and considered frivolous. But this has certainly not been the case in the last decade or so. In academic circles the subject is flourishing. Publishers like Bloomsbury have catalogues saturated with books on the topic. This said exhibitions of women’s fashions are huge drawcards, suggesting women are still objects of desire as opposed to subjects of analysis. Countering this are the many women who have in recent times written seminal studies on the complexities inherent in dress/fashion and forged new pathways for the study

What does dress provide us as a tool for examining women’s lives?

With respect I think this is only half the question that should be asked. Dress provides an extraordinary useful method to explore the nature of any culture and to examine both the lives of men and women and their relationships. In place of the old single time line of style or cyclical change, dress provides an entry point into any culture, its social interactions, commerce, sexual mores and is a key indicator of identity. Dress allows us to interpret the history of men and women in a unique way.

You are also interested in the dress practices found in other cultures, such as Aboriginal Australians and Pacific Islanders. Does dress studies, as opposed to fashion studies, allow historians and theorists to take a wider, cross-cultural view? Fashion can of course be very Westernised in its focus.

I feel that reinforcing the notion of a gap between dress and fashion studies is not necessarily productive. Cross disciplinary research appeals to me as more useful. I also think the answer to the question lies in how one understands and uses terminology. Under the rubric of dress one can certainly include analyses of Indigenous clothing and associated practices, that of Islanders and indeed so called ‘ethnic’ attire. But non-Western dress also expresses wealth and status in its own ways. Fashion with a capital F is driven by Western interests, global commerce and creation of novel products in order to increase consumption. Fashion with a small f is closer to a fad or slight alteration and this latter does inflect both customary dress and less obvious kinds of wearing and bodily adornment. We know customary dress is not stylistically static and, to varying degrees, incorporates new elements and slight shifts in style. So nuances in both fashion and dress can be considered in non-Western attire.

I believe you grew up in South Africa and initially worked as a costume designer. Was clothing and dress something that you were always drawn to? Were there many opportunities in those days to pursue dress history?

Since a child in South Africa I loved clothes and dressing up—a passion was collecting paper dolls. I trained in so called ‘Fine Arts’ but was always interested in ‘the Decorative Arts’ which were less prestigious than the former. I was fortunate to get my first real job with the State theatre company mainly making theatre, opera and ballet props. I was catapulted into designing costumes for major opera shows in Johannesburg and teaching theatre design with no prior training. There were no opportunities at all to study ‘dress’. It was a question of teaching oneself. The only other person I knew interested in dress was a woman artist recording tribal African attire in remote areas. I admired her work and would have liked to have taken this further but felt her lifestyle too dangerous.

You left South Africa in the 1960s after winning a highly coveted place to study at the Courtauld Institute in London – this was one of the only formal costume history courses at the time. It was run by Stella Newton, who was pioneering in her approach to studying dress using paintings and art history. Can you tell us about that? What was she like as a teacher? Has her approach remained with you?

As a student of ‘costume’ I felt totally at home. Stella was a marvelous and inspiring teacher. Her focus was painting and sculpture as a source of information on dress. We started with lectures on the Greeks and progressed up to the 19th century. She was less keen on contemporary dress. The visual source was our primary evidence in her view. But she drew from a wide range of information, especially art history. She was interested to contextualize dress and used archival and other social and historical material as supporting evidence. We were alerted to all classes of wearers. (She was especially interested in European so called ‘peasant dress’). She taught us to date paintings extremely accurately, something I can still do. This technique was useful to art historians and dealers who needed to give art works (with limited provenance) as accurate a date as possible. We were also asked to determine if works of art were fakes or not. Stella believed that forgers often got the dress of a period wrong where they could calculate painting style and other things more accurately. There are art historical precedents for this in the work of a 19th century scholar called Morelli. She made us feel we had special abilities.

I have since taken a different path. Whilst I had a matchless education, I don’t like chronological approaches to high-end style and I like to integrate material culture to a greater degree. Surviving dress interested Stella but in a slightly limited way. Unlike her I see much value in theoretical approaches especially related to material culture, consumption, etc and I feel that ethnography and anthropology have much to offer the subject. I aim where appropriate to forge links between material objects, theoretical considerations and what I know of visual sources. I am probably more interested in the dress of everyday life than Stella. Perhaps one reason I took a different route was because Brisbane has fewer examples of early international art than were available to me as a student in London.

You came to Australia in the 1970s and began working at the University of Queensland. There you pioneered fashion and dress courses and began serious research about Australian dress. Even today dress and fashion research in Australia is still emerging, but I imagine it was really an entirely new field when you began. What were those early years like?

When I first started at the University I was employed to teach art history. I did not teach dress studies for some years. The topic was seen as quite bizarre but it soon gained a bit of a following especially when I leaned more toward teaching fashion. Many people felt and perhaps still feel that they are qualified to discuss dress/fashion where they do not talk about other specialist areas such as archaeology. People wear clothes and thus consider themselves experts. This led to the perception that the subject could easily be dismissed as light on and also to a sidelining of dress/fashion expertise.

I was extremely lucky to feel I was the ‘first’ to look at certain archival material, literature and imagery from this new perspective. But it was isolating and my work was something of a curiosity. I did give papers at art and history conferences but I did not have the reassurance of a particular discipline behind me. On the other hand coming new to Australia from a conservative country, I found a critical openness in students that was refreshing.

I think you even had a radio program on the ABC? I often think there should be more radio and television programs about fashion and dress. What kinds of things did you cover?

Beginning in the 70s I was asked to do question and answer programs with one of the local announcers. They were comments on current trends in dress, or I answered questions on the origins of different types of clothes. I did one series of six on dress and identity. It was taped and one ran each week. I also did a taped radio program on dress of PNG where I had lived for a year. Over the years I have done a great many interviews on current dress. Some were round table interviews with different ABC stations and other experts. If some unusual dress was worn in Brisbane for the first time, perhaps new uniforms for Queensland Rail employees etc, I would be asked to comment. I worked on a film shown on the ABC a few years ago. It was very disappointing as it skated over the interesting issues in Australian dress. I also think far more should be done, but there is a tendency to go for superficial issues, rather than the really significant aspects of dress/fashion which I consider more interesting.

You’ve published widely. I wonder which books or articles you have been most proud of?

My book Fashioned from Penury (1994) did fairly well at the start but interestingly it has had a bit of a revival in the past few years. I am proud of this as there has been no equivalent publication. I am also very proud of the volume I edited for the Berg Encyclopaedia of World Dress and Fashion (2010) which was extraordinarily challenging. I am also proud of Dress and Globalisation (2004), the first book to discuss dress and sustainability, and the essays ‘The Fashion Photograph: An Ecology’ in Fashion as Photograph Viewing, and Reviewing Images of Fashion ed Eugénie Shinkle (2008) and ‘The Mystery of the Fashion Photograph’ Fashion in Fiction. Text and Clothing in Literature, Film and Television eds Peter McNeil Vicki Karaminas Catherine Cole (2009) – a transcript of my keynote paper given at the ‘Fashion in Fiction’ conference in Sydney.

It is fairly hackneyed territory, but you also have a fine arts and art history background. I wonder what you think of the art versus fashion debate. Do you see fashion as art? What about dress?

This is quite a fraught area of debate for which there are no simple answers, as with the art/craft debate. Consumers certainly experience art and fashion differently and they have different value systems but many artists, for different reasons, have been designers of fashion. There have been frequent slippages and synergies between the two practices but also antagonisms. Both fashion and clothing/dress can be exhibited as installations in art galleries but does this make either ‘art’? ‘Putting oneself together’ in terms of dressing the body is akin to a personal art, and fashion and art have at times found themselves mutually useful. The answer to your question is not straightforward in any way.

You’ve been working with fashion and dress across a period of dramatic growth within museums, universities, libraries etc. I wonder if you could comment on how the study of dress and fashion has changed?

When I started out the study of dress and fashion was a great novelty. It was as if one could research in any area and opportunities were endless. Today publishers have almost overdone the subject and it is difficult to carve out an entirely new specialist area. Naturally the internet has made a huge difference to image access as well as access to other forms of information. In my early years of teaching there were practically no articles or books I could recommend to students. Now there is a huge range of material which is wonderful. Cultural Studies, Media Studies, Material Culture Studies, Women’s Studies, Ethnography and associated Critical Theory has lifted the bar in studies of dress and fashion. Without interdisciplinarity the area would have remained limited and esoteric. In Britain after I had completed by study, there was a strongly conservative attitude but this has changed dramatically.

What do you think the future is for fashion and dress studies? What are you currently working on?

I hope that fashion and dress studies has a great future, especially in links with Material Culture Studies and Ethnography, even Archaeology. In some ways I feel too much has been published too quickly but many books are of a very high standard. Fashion is extraordinarily popular. One can see this in the crowds who visit fashion exhibitions and clearly museums use fashion as a draw card. I think that this is excellent, especially if displays are inventive. But it is important to also stand back from the glitzy aspects of fashion and look for other narratives that clothes can offer.

At present I am working on a project on Dress and Time. I am considering how the cultural phenomenon of time explains dress practices around the globe, given the vastly different socio/cultural, political, religious and imaginary concepts about it existing over millennia. Reflecting on the temporal in the widest sense shows how time has been coextensive with how, when and why humans design, fabricate, wear and preserve all forms of garment, fabrics and accessories.

Nadia Buick is a fashion curator, writer and researcher based in Brisbane, Australia. She recently completed a doctorate in fashion curation and is currently Co-Director of The Fashion Archives.