Interview with Laura Sansone: Fashion + Sustainability – Lines of Research Series

/by Mae Colburn

One of Sansone's two Textile Labs, which she carts to greenmarkets in and around New York City.

Laura Sansone readily acknowledges that she comes from a “crafty background.” She received her B.A. from the Philadelphia College of Art and her M.A. From Cranbrook Academy of Fine Art (both in Fiber). Now, at Parsons' School for Design Strategies, she teaches spinning and dying, organizes field trips to fiber farms Upstate, and takes students to greenmarkets in and around New York City as part of her mobile Textile Lab. For Sansone, “crafty” means more than technically adept or playfully skillful; it signifies a thoughtful, soulful, tactile appreciation of material productivity.

Mae Colburn: I’d like to begin by asking you about your relationship to this word, sustainability.

Laura Sansone: When I think of sustainability, I don’t just think of environmental issues. I think of the socioeconomic aspects of sustainability, and how to enrich communities through material production. Also, looking at who is making the work and where the materials originate. It’s really about designing with transparency, about realizing the interconnectedness of products and systems, and finding alternatives to commercial production. I think one way to do that is to think about things in a decentralized way, in a way that’s more local, so that communities are more in control of production and consumption.

MC: Could you describe how you arrived at this interpretation?

LS: I started becoming interested in sustainability when I moved to the Hudson Valley in 2003. My partner and I bought an apple orchard up there, and our neighbor, a local farmer, started farming our land and selling at greenmarkets here in the City. So I started to realize how these resources in Upstate find their way to the City, and the importance of venues like greenmarkets. That’s when I began thinking of ways of linking the things that I do [with fiber] to farming.

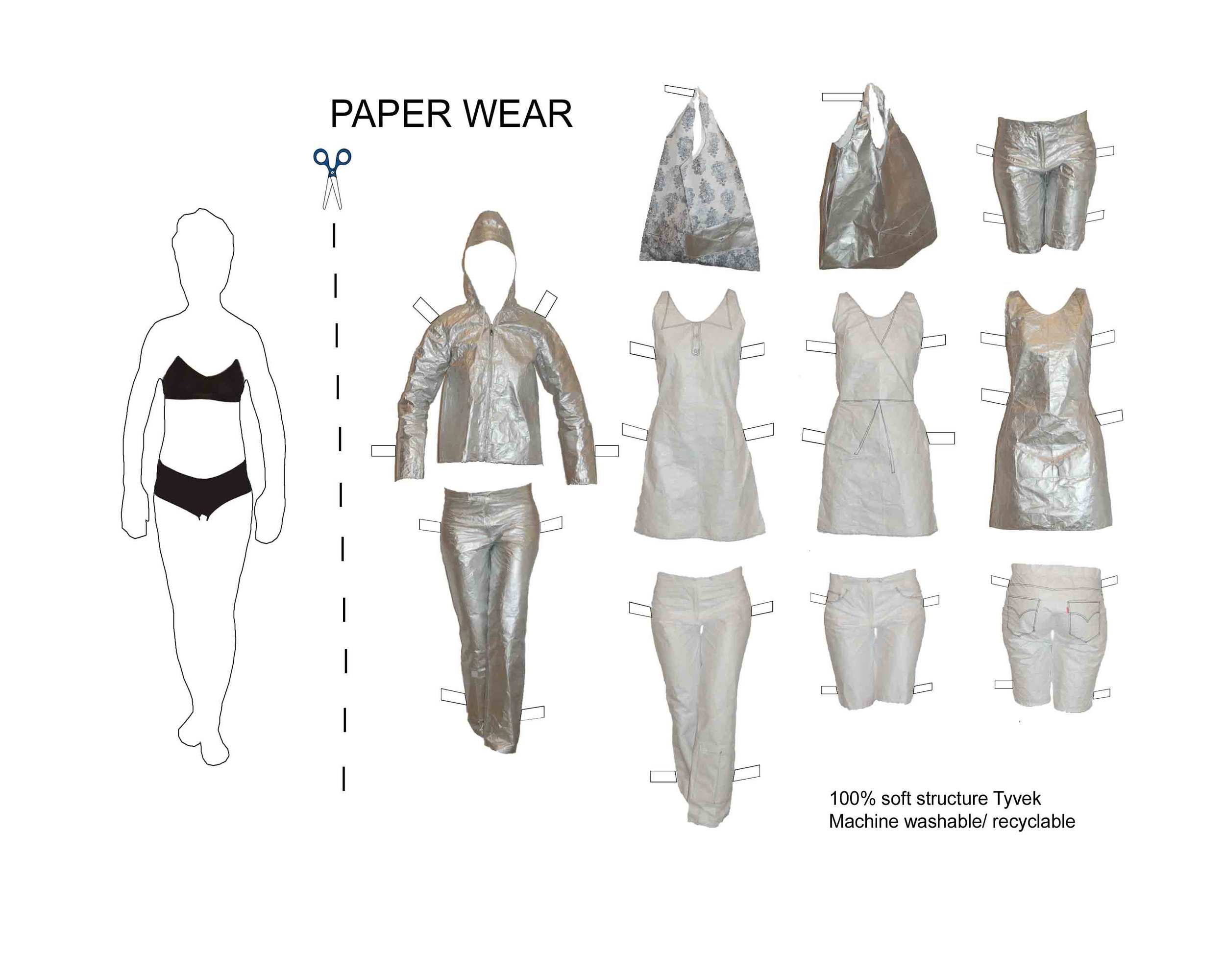

I was working with Tyvec at the time, so I was already interested in no-waste production. It’s a recyclable polyethelene material with many applications (envelopes, hazmat suits, even high fashion back in the 1960’s in sort of a playful way). I was sending my cutoffs back to Tyveck for recycling, and asking consumers to do the same. The products folded up into envelopes so they could be sent back to be recycled. So I was already thinking along those lines. Once I moved [to the Hudson Valley], I decided I had to go beyond that and try to use natural materials so that everything could be composted. That’s when I started working with organic cottons and natural dyes and that led me to investigate local materials. That’s when I realized that there were fiber farms right up there in the Hudson Valley, and a really active fiber community.

"Paper Wear," Sansone's line of recyclable Tyvec clothing.

Years ago, everybody had a spinning wheel in their house, and a loom. Families and villages were really self-sufficient, and while I’m not saying that that [model] is the answer to our global problems, I do find that handcrafting is a way to bring people together. There’s this cohesive nature to it, a real social connection that transcends age, gender, race, economic status. It’s amazing. That’s what I find when I take the Textile Lab out to greenmarkets. Everybody has a story about something that their mother used to knit, or all the yarn they have in their basement, or about how they’re addicted to crocheting. It’s an activity that reminds people of their past. It excites people. Maybe production can happen on a smaller scale, and maybe it can be supported by communities. You know, there’s a certain social importance to being able to produce as a culture, and I find it problematic when a culture stops being productive in a material way.

MC: It seems like every decade experiences a resurgence of craft in some form or another. How would you characterize what we’re experiencing today?

LS: Bauhaus was all about that. Arts and Crafts was all about that. There are these movements in art and design that have to do with seeing an imbalance and searching for a more assertive equilibrium among producers and the way things are made. It does happen frequently and it’s mostly this convergence, these moments in history where craft and design and art converge; right now we’re at this point where there’s a convergence. I call it vernacular craft. That is, more like folk crafts, where designers are really lifting folk methods and adapting them, using them in their designs.

MC: Could you describe the Textile Lab in a bit more detail? You’ve got a cart…

LS: Yes, a cart, and there’s a shelf that comes out in the back and a stove that sits on top. Inside, we have all of our equipment to make dyes: pots, a scale, and a blender to make paste.

MC: What do you do about electricity?

LS: When we bring it to the park, farmer Joe (the farmer who farms on my property) brings a generator for us and sometimes we can plug it in at an outlet in the park, so we find a way.

I have another lab that I received funding for from City Atlas, a project with City University of New York and Artist as Citizen, a smaller one. I spent a good deal of last spring, summer and even fall taking the smaller lab to neighborhood greenmarkets all over the City. That one has gas burners.

MC: There’s something I really love about your Textile Lab idea, especially in the context of education. You’re teaching students these techniques, then taking students with you to greenmarkets around the city where they teach these techniques to the public. It’s almost viral.

LS: This stuff happens online all the time; there are even social networking sites specifically on handcrafting, like Ravelry. But there’s a social component to going out and making it happen in an organic context like New York City, especially a place like Union Square where people are constantly coming and going. People stop and talk to you, trade stories, share knowledge. We bring the Lab out to the Union Square greenmarket and students just lure people in. Once we had a hearing impaired group come up to the Lab. So there I was trying to explain what we were doing, pointing to things, flailing around, and then all of a sudden one of my students walks up and starts signing. She knew Sign. I was so happy. We had another woman come over, she was from Algeria and she didn’t speak a lot of English, but we gave her a drop spindle. It was a top whirl spindle, and she was trying to spin with it, but we could tell she wasn’t that happy with what we’d handed her. Then we realized she was actually used to using a bottom whirl spindle, the kind that you spin near the ground. We also had a guy from Tibet come up and show the students how to spin on a stick, just a stick, probably like he’d been taught as a boy. Children also come over, especially at Union Square because they have all sorts of educational programs. It’s wonderful, a really nice inclusive moment for everyone.

MC: What would you like to see markets like this become five, ten years down the line?

LS: In my world, I would love to see the market become more than just a greenmarket. To become more like a real marketplace, selling fabric, and handmade shoes, handmade kitchenware, a place of real material commerce in the sense of material goods (not just consumable produce). The market is becoming that way to a certain degree. Something really natural happens there where there’s this sort of bartering that occurs, and I think that’s so important. Like, “I have this, you have that, let’s trade” (the farmer does that with us, he gives us food and farms our land, he brings us bread from a guy at the market who he trades with). You have to produce in order to engage in that sort of economy, but again, a productive culture is a strong culture so it goes hand in hand.

Laura Sansone is an artist, designer, and adjunct professor at Parsons the New School for Design's School for Design Strategies.

Mae Colburn is an independent textile researcher based in New York City.