Interview with Christina Moon: Fashion + Sustainability—Lines of Research Series

/by Mae Colburn

Image taken during fieldwork research: shoe factory assembly line, China, 2007

Christina Moon joined Parsons’ School of Art and Design History and Theory faculty this past September with a freshly minted doctoral degree from Yale’s Department of Anthropology and a markedly holistic perspective on the fashion industry. Her practice involves going out, interviewing people, and thoughtfully translating these stories into broader global narratives. Her PhD dissertation, Material Intimacies: The Labor of Creativity in the Global Fashion Industry, brought her everywhere from kitchen tables in Los Angeles, to shoe factories in China, to what she calls the “fashion streetscapes” of New York City and beyond.

Mae Colburn: Could you describe how you arrived at the theme of Material Intimacies?

Christina Moon: I was interested in writing about this larger historical transformation, these larger cultural phenomena that were going on, and tying these to the personal narratives of the people I was meeting, interviewing, and working with in the fashion industry. That, for me, was the greatest challenge of my dissertation, but also the most fulfilling one: how to bring out the stories of individuals and their experiences, but in a way that they would not simply be dismissed as ‘drop in the bucket’ personal, or anecdotal, stories. I wanted to show how these individual stories were part of much larger ones about the history of fashion and clothing, but also the history of political, economic, cultural, social movements occurring around the world.

So, for instance, during my fieldwork, I spent time with families working in the informal clothing markets of the fast-fashion industry of Los Angeles, which are dominated by Korean Brazilian Americans (if you can imagine that!). They’re Korean clothing traders who left Korea in the 1960s and, because they couldn’t get visas to the United States, ended up in South America (mostly in Brazil), where they imported textiles from Korea, set up cut-and-sew factories in Brazil, and sold their designs in markets they created. They raised their children in [South America] but, because of the uneasy economic and political climate of the 1990s, moved with their children to Los Angeles in the late 1990s. Now, many of their children consider themselves Korean Brazilian Americans. […] These families run the informal clothing markets of L.A., which have become, within the last decade, the main hub for the design and distribution of the majority of fast-fashion within the U.S. and across the Americas in general.

The matriarch of this one family, whom I spent quite a lot of time with (she was really in charge of the family business), spoke to me at length about her experience working in the fashion and garment trade over the last three decades [on these] three different continents. Her stories revolved around lace because when [she and her family] first came to the United States, it was by selling her lace designs. She was only able to make one connection to a vendor, and he was a lace vendor, and so for her first three years here, that was basically how she supported three children, a husband, and her mother-in-law. It was so interesting because that story only came up after she had shown me photos of her daughter’s wedding, and explained how she had created her veil out of lace. It all came out as her personal story, but it still illuminated this larger history of changing economic and production systems in the globalization of fashion.

I wrote some of this in a piece [titled] Intimate Materialities. I’d been told throughout graduate school that there wasn’t any room for narrative in anthropological writing, that those days of narrative ethnographic accounts were long gone with The Nuer and The Golden Bough, and that books were part of a capitalist market, which liked things delivered as neat, tidy, and under a certain number of pages. But I felt like without narrative, this story and history wouldn’t be interesting at all. I knew I could deliver this history through statistics, in huge broad strokes about the globalization of fashion through trade laws and political economy, but I felt like when I read those histories, I had a hard time finding my own personal way in. Before I got my job at Parsons, I had put out a handful of job applications and got an initial interview with the University of Texas in Austin, Anthropology Department. There’s a really incredible anthropologist there named Kathleen Stewart who interviewed me along with other members of the department. I had to give all these writing samples and chapters of my dissertation for the interview (which I didn’t think they’d read so thoroughly) but when it came time for the interview, it became apparent that Stewart had read every single word that I had written, including the narrative [described above]. When she asked me what kind of classes I would be able to teach, I said ‘I can teach this or that…’ and rattled off a list of traditional anthropology courses, but she said ‘No, no. What about teaching a class called Intimate Materialities. That’s the part of this dissertation that I really liked. That’s the kind of history we need to be writing.’ And that gave me fuel and a newfound sense of confidence. From there, I developed this idea that ‘intimate materialities’ which means that the materials are ‘intimate,’ but if you switch it around to ‘material intimacies,’ the base of that phrase is the word intimacies, which is important because the dissertation I ended up writing was about relationships between people in an industry often described as impersonal, anonymous, and economic, [and] how clothing and fashion become the mediation or form in which all these relationships take place – across generations, across continents, across cultural divides.

MC: How would you position this practice, narrative writing, within the scope of fashion and sustainability? Do you see your role as more practical or more theoretical?

CM: I think both are really important to my research and to understanding issues of fashion and sustainability. Practice for me means going out, interviewing people who are part of the process, understanding why they make the decisions that they make, their values within these systems, and where they belong within this enormously complex global process that’s constantly changing, full of kinks and complications. […] Interviewing people always keeps me hopeful. People are always trying to figure things out, no matter how challenging and trying their lives and situations are. Theory for me is about the universal, the conceptual, the importance of the metaphor. It allows me to understand issues of fashion, globalization, and sustainability alongside other moments in time, history, in other industries. […] Regarding sustainability, I’m actually just beginning to learn more about this word. I was just on a panel on fashion and sustainability recently and I said on the panel that [while] I was really interested in the history of this word, I was really more interested in other words.

MC: Which other words do you identify with?

CM: The words that I identify with are pretty old school, like quality of life, viable futures, self and collective preservation. ‘Sustainability’ […] brings up more questions for me than answers. Who’s deeming what more, or less, sustainable? With the communities that I’ve spent time with, people have been looking for sustainable solutions forever, so there’s something very sinister and very patronizing about that word. I feel quite ambivalent about it. Also, what does sustainability mean if it’s not accessible to everyone? I think communities have long tried to figure out how to provide for one another. That said, I really hope for a more sustainable future.

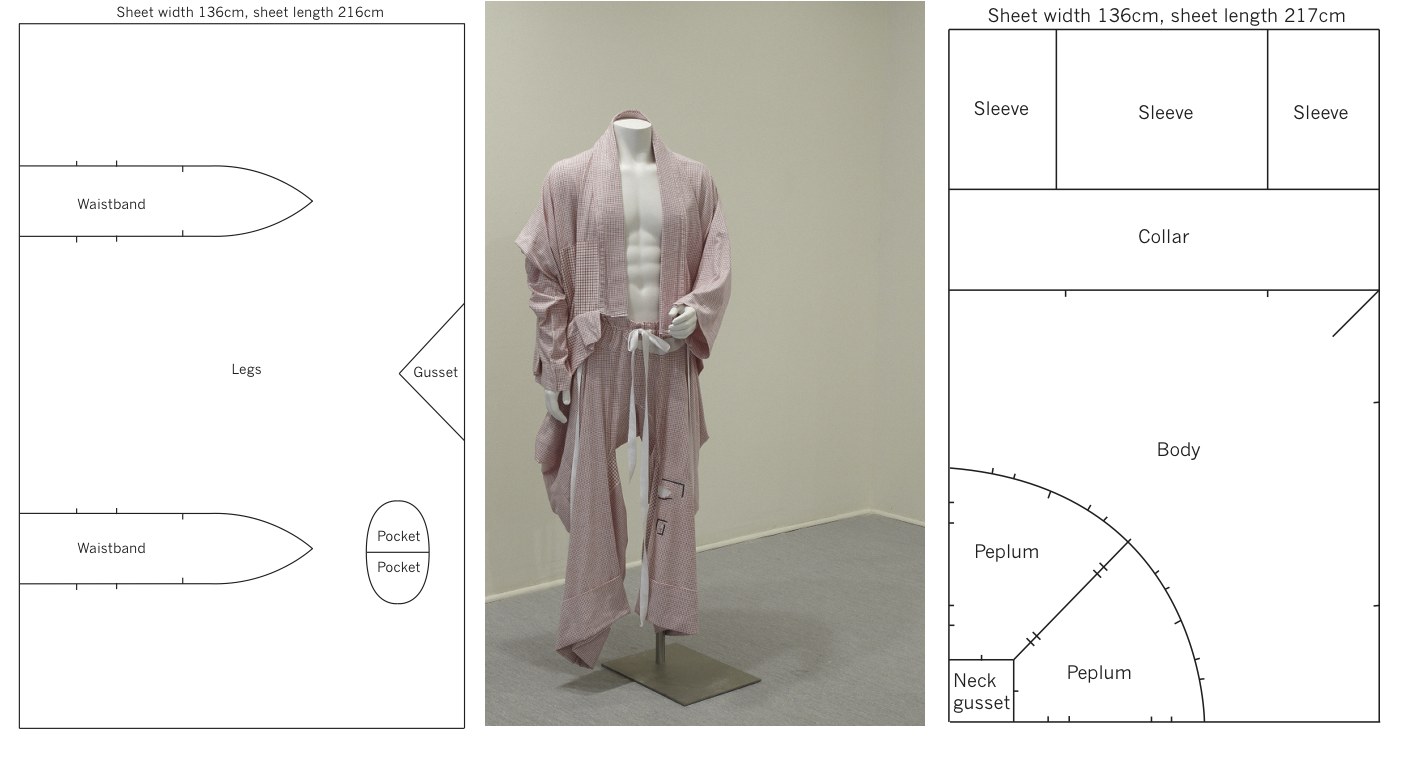

Image of the New York Fashion Week Fashion Calendar taken during fieldwork research in New York City, Spring/Summer 2007

MC: That raises a good question about sustainability within the social sciences. Often, the term is couched within the natural sciences, or like you mentioned, economics.

CM: Every discipline has its own catch phrases and perhaps within the social sciences [sustainability] has been called other things. I don’t think it’s as popular [in the social sciences] as it is in a place like design, particularly at [Parsons] because here, we’re surrounded by practitioners who are designing and creating constructed environments; there’s a built, material, and designed element to it. In anthropology, there’s more of a trend towards the social, towards human equality, justice, and rights. We’re talking about different industries and disciplinary fields, and so the language changes.

MC: I wanted to turn now to your teaching. You’ve been teaching at Parsons for a year now and I’m curious how your relationship to education has shifted, having started in anthropology and now teaching in fashion studies.

CM: I’ve always been interested in educational reform. When I was at school [at Yale], I really sought out professors, students, people who were actively creating alternative spaces within and outside the university. I was in a meeting once with my main advisor at Yale (his name is David Graeber) and at one point he said, ‘I’m your teacher; you’re my student; now I’ve told you everything I know, so now you know everything that I know, so now we’re equals.’ And that sense of a mutual relationship – of mutual mentorship – was really inspiring to me. I try to mirror that in my classroom here at Parsons, making it more of a collaborative space. I teach undergraduates and graduate students, people who will graduate and get jobs in these fields, so I’m very conscious and aware of that, constantly reevaluating the worth of what I’m introducing because I want to give students something critical, something that will allow them to see that this word ‘fashion’ as a lot larger, bigger, more political than they could ever imagine. We’re talking about so many different complex systems: formal ones and ones outside of any formal system. As graduate students in anthropology, we could say ‘we are activists, our role is to say no to corporate culture, no to industry,’ but this is something that gets thrown out the window when you’re at a place like [Parsons] because students have to get jobs within these industries, pay back their school loans and make a living. So now, the challenge is, how to critique from where you are? How to critique from the inside and to make it better? How to recognize the complexity of it all? That’s been both a challenge and one of the most rewarding things about being here at Parsons, constantly asking myself what kind of impact students will have on the industry with this knowledge.

MC: Could you comment on the role of ethnographic field research within the fashion industry?

CM: I’m still grappling with what ethnographic field research is. I say that I do it. People tell me that I do it, but I’m not exactly sure because the things that I’m attracted to, and the things that I read, explode this idea that [field research] is the privilege of anthropologists and ‘trained experts’ only. But I do think that it’s a little different than swooping in, getting your sound bite – your quote – and leaving. I think today, ethnographic field research implies a sense of trust, the development of a mutual relationship, even if it is full of its own politics, and self-reflection on one’s own position of power and privilege. There is very much a sense of long-term community engagement. I still find parts [of anthropology] to be problematic, sticky, political, but I do think it’s a way to get at perspectives, especially on contemporary phenomena, that you’re just never going to find in history, or in the archive, or in a secondary text. You’re never going to find [this type of information] in a book, museum collection, library or historical archive, so your only choice is to seek people out, spend time with them and interview them, and learn from people who are working within the industry. […] We need ethnographers to go out there and collect these oral histories, engage with varying communities in fashion, be a part of and express these worlds that are constantly changing.