Interview with Otto von Busch: Fashion+Sustainability—Lines of Research Series

/

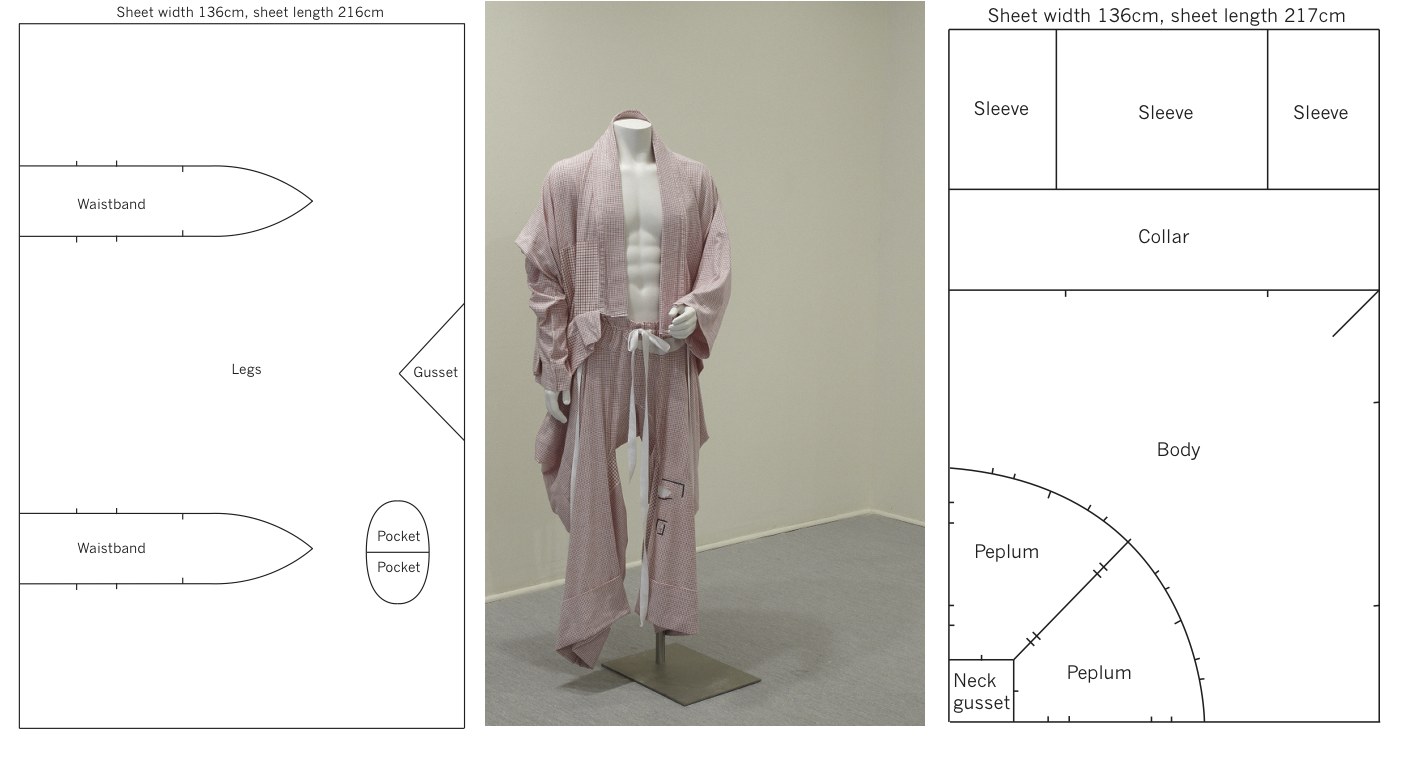

“In your skillful hands, the sewing machine is a tool for liberation!” reads a passage on Von Busch’s website, where users can download everything from ‘zines, to toolkits, to recycling "cookbooks" such as the one featured above. Cookbook by Otto von Busch.

Otto von Busch is a craftsman, researcher, and activist. He joined Parsons’ Integrated Design Program (IDC) this past September and has since become the natural cynosure of a lively conversation about fashion and social engagement. His website,>SELF_PASSAGE<, features essays on topics ranging from mending, memory, and mindfulness, to spirituality, cyberspace, and sustainability. He speaks English with the lilting, faintly lyrical accent of a highly spirited Swede and has the remarkable ability to detect and demystify subtle metaphors buried in otherwise familiar words (fashion-able, sustain-ability). He is, in short, a master of remastry.

Mae Colburn: You completed your PhD, “Fashion-able: Hacktivism and Engaged Fashion Design,” at the School of Design and Crafts at the University of Gothenburg in 2008. Could you describe how you arrived at that topic?

Otto von Busch: I started studying different crafts at craft schools in Sweden after finishing high school. I really wanted to become a guitar builder, so I was studying carpentry and cabinet making, building guitars, restoring mandolins, banjos, and those sorts of things. Then I decided I should try something else, so I went to another prep school for printing and weaving and started taking patternmaking and sewing classes. But after a while it all felt very introverted, so I started studying art history. I thought ‘ok, I can try this for a while,’ and I got sort of stuck and studied art history for many years.

Later, I studied at a program called Material and Virtual Design (sort of interactive design and industrial design coming together) at Malmo University in Sweden, and that’s how I got into more ‘computer-ish’ thinking. That came together in trying to understand how open source, hacking, and open platforms could apply to fashion. I was recycling clothes and thinking about how I could produce fashion recycling programs (I called them 'cookbooks') that people could download, where people could follow my simple instructions but apply them to their own projects, like what was happening in hacking, Wikipedia, Linux, where the user was suddenly engaged as a collaborative knowledge producer – where the user’s knowledge is acknowledged.

So the question became, how could designers encourage people to become designers themselves, so that fashionable meant not only dressing people fashionably but also making them fashion-able – how could that engagement happen? And as a designer; how could you merge that sort of network thinking about open source with fashion? That’s how it came together at the end of my studies, which also became the theme for my PhD.

MC: You discuss Paolo Friere’s Pedagogy of the Oppressed and John Dewey’s Democracy and Education in your PhD. Could you go into more detail about how educational theory influenced your approach to fashion?

OVB: Of course they were influential as I tried to see how fashion could be turned from a phenomenon of passivity, or of very limited choices funneled through our socio-economic position, into a more liberating or capability-building process. I’m especially fascinated by the heritage of sloyd, the heritage of craft education, or shop class, and how that emerged in the mid 19th century – Friedrich Fröbel and the Kindergarten movement, and the birth of the Montessori school and these sorts of alternative pedagogical models that are very much about producing craft skills, hand-eye coordination, having agency in the world, agency because you are learning how to produce things, how to fix things.

It comes down to basic freedoms: if I know how to fix my bike, I have a choice that I didn’t have before. Knowing how to do something also produces another attendance to the world, another attention, another awareness. If I, as a designer, teach people to reclaim the sewing machine, they can also learn to see the complexity of the details of clothing – they can recognize good craftsmanship, and that’s an agency of empowerment, I think.

MC: I've noticed that you're often described as a heretic, demagogue, hacker, subversive – kind of a ‘bad student.' And, indeed, much of your work in fashion is about subverting, questioning the system. How does this role translate into your experiences teaching at institutions such as Parsons?

OVB: Those terms are a little provocative of course, but at the same time, as I write in my thesis, a heretic isn’t necessarily an infidel. It’s somebody who uses the system to give way for liberation. Also with demagogue, hacker, I try to put the emphasis on constructive critique, or positive change.

From a pedagogical perspective, working with social engagement in general can be very tricky within the academic industrial context, but that said, you have to create your own free space. I think it was a student of Georg Simmel who wrote about his lectures that he felt as though he was at a place where thought was being born, not where thought was being repeated. I love to do projects like that, where I’m as curious about something as my students, and I hopefully manage to convey that curiosity in a structured way. I’m lucky at Parsons that some of the courses in Integrated Design allow that space to happen. Currently, I’m leading a course called “The Gift,” where students set up Etsy stores, but also challenge the borders of what’s sold on Etsy. Could you sell services? How can you find your own independent voice within a standardized framework like Etsy?

In Otto’s Community Repair Project at the London College of Fashion (2011), students explored the social dimensions of home sewing by collaborating with community members to repair unused clothing. Garments by Rachel Clowes (top) and Renee Lacroix. Photos by Otto von Busch.

MC: You use two phrases throughout your writing that seem to define a certain pedagogy – ‘small change’ and ‘action spaces.’ Could you give us some examples of how these ideas come through in your teaching?

OVB: You’ll have to come and see. Some of the latest projects have turned out really well, such as the Community Repair project with MA students from Fashion and the Environment at London College of Fashion. We used garments in need of mending as probes for students to get to know their neighborhood and their neighbors. Instead of leaving it to the tailor or just throwing it away, how could you engage your neighbors in the repair by barter service in a site-specific way? It produces all these histories, sort of a narrative litmus paper, and brings out local qualities. Of course it’s a small change, but as a fashion designer, how could I set up a brand that would actually work exactly like that? A brand that produces new local action spaces rather than only happening within the commodity economy?

MC: Could you say a few words about how your work relates to sustainability?

OVB: I don’t talk about sustainability in my work, and if I do, I usually talk about abilities and the ability to sustain values. I think that we have to disseminate abilities, whether it’s the ability to repair, or the ability to have attention to detail, or the ability to use the sewing machine. It’s about building those capacities rather than disseminating the commodities. How do we produce the ability, the courage, to dress and interact with the fashion system differently?

Otto von Busch is Assistant Professor of Integrative Fashion at Parsons the New School for Design. He holds a PhD from the School of Design and Craft, University of Gothenburg.

Mae Colburn is an independent textile researcher based in New York City.