Interview with Timo Rissanen: Fashion+Sustainability—Lines of Research Series

/by Mae Colburn

When I met Timo Rissanen, he was fielding a flurry of emails and phone calls. His office was crowded with books. Sample garments were piled next to the door. The arrangement was clearly deliberate, testament to his belief in the productive synthesis of research and design. Rissanen is one of few academics globally to bear the word 'sustainability' in his title. He developed the idea of Zero Waste fashion in his P.h.D. dissertation, “Fashion Creation without Fabric Waste Creation.” Now, he’s teaching Zero Waste at Parsons the New School for Design, where he is Assistant Professor of Fashion Design and Sustainability.

MC: How did sustainability inform your own education?

TR: Zero waste fashion design started for me in 1999. We had to do a written dissertation in our final year of undergraduate before we went into final collection, and mine was on Madeleine Vionnet and her influence on Issey Miyake, John Galliano and Claire McCardell, and myself. I actually wrote in the conclusion that it might be possible to design clothes without wasting any fabric. After graduating, I went into industry, had my own label for a few years, and worked for a few other people. Then in 2004, I decided to put the label on hold and got interested in postgraduate study. […] It’s been just over seven years now.

It’s been interesting the shift over these seven years, too. People were skeptical [of zero waste] in the beginning. Things like ‘I’m not sure it’s possible to design without fashion waste.’ Or whether it’s possible within the industry from a cost point of view. And also a very valid point about the much bigger problem of waste connected to the level of consumption, the idea that we don’t hang on to the clothes we buy. When I started my PhD, the main focus [in fashion and sustainability] was on materials. That’s still important, but it’s just one piece of a much bigger picture: the fashion industry as a system, fashion consumption as a system, human culture as a system.

I would encourage more fashion designers to get into research, although it’s still a fairly new thing. That’s been one of the responses from people [regarding my PhD]: “I didn’t know designers could do a PhD.” It’s sort of a duel challenge because if you look at fashion design in an academic context, it’s done a pretty good job of isolating itself from other design disciplines, so there’s loads that’s been written about design theory over the past 20 to 30 years in particular, but most of the time fashion design doesn’t enter the conversation. I think it’s partly the fact that fashion has lived this very insular existence. Even with the way that fashion media writes about itself or writes about the industry (and particularly fashion designers), there’s a lot of myth building about the practice of fashion design.

MC: Do you feel like there are enough educational resources available to teach sustainability?

TR: When Kate Fletcher’s book came out four years ago, it filled a massive gap, as did the book by Janet Hethorn and Connie Ulasewicz, which I was in as well. Before then, apart from some conference papers and journal articles, there was very little [on fashion and sustainability] in terms of books. I had a book out last year with Alison Gwilt, and I know that Kate Fletcher has a book out this year with Lynda Grose. They’re really the two people that I look up to because they’ve been doing it for two decades. They’ve been so generous with information, recognizing that the problems are bigger than us as individuals and any of the institutions that we might work for and also bigger than any one country. The industry is global. The really tough problems cross boundaries on so many levels. It’s going to take collaboration.

MC: In terms of educational infrastructure, it seems like there are some very strong sustainable fashion programs in England. Am I right?

TR: The London College of Fashion had the first MA program in fashion and the environment but Parsons was quite forward thinking in that sense, too, in that they started advertising the role that I’ve got in 2008. Apart from Kate’s role at LCF, which is Reader in Sustainable Fashion, I think my position is one of the few still globally where the word ‘sustainability’ is actually in the title. I also know that within a couple years, sustainability will be implemented into all of Parsons’ core courses. Quite often, sustainability has had to reside in electives or students get introduced to it in their third or fourth year of study, but really it has to be present from the ‘word go.’ It’s going to be consistent from 2013, and it’s going to be part of the education that everybody at Parsons gets.

We’ve had increasing numbers of seniors taking sustainability on of their own volition. I’m also aware that in the junior and sophomore years there is an increasing number of students that are interested, which is fantastic because they are the future. I feel very optimistic for the industry. That’s the beauty of teaching, really. You see these young people that are so passionate and so committed to keeping what’s amazing and what’s beautiful about the industry but then really working on the things that aren’t. That’s how I see the next 20 to 30 years: trying out lots of different solutions to lots of different problems. It’s going to take us at least 20 to 30 years before we have an industry that’s really about producing beauty in all its aspects. That’s how I look at things now: let’s create an industry that’s about creating beauty, and not just beauty in its garments, but beauty all around.

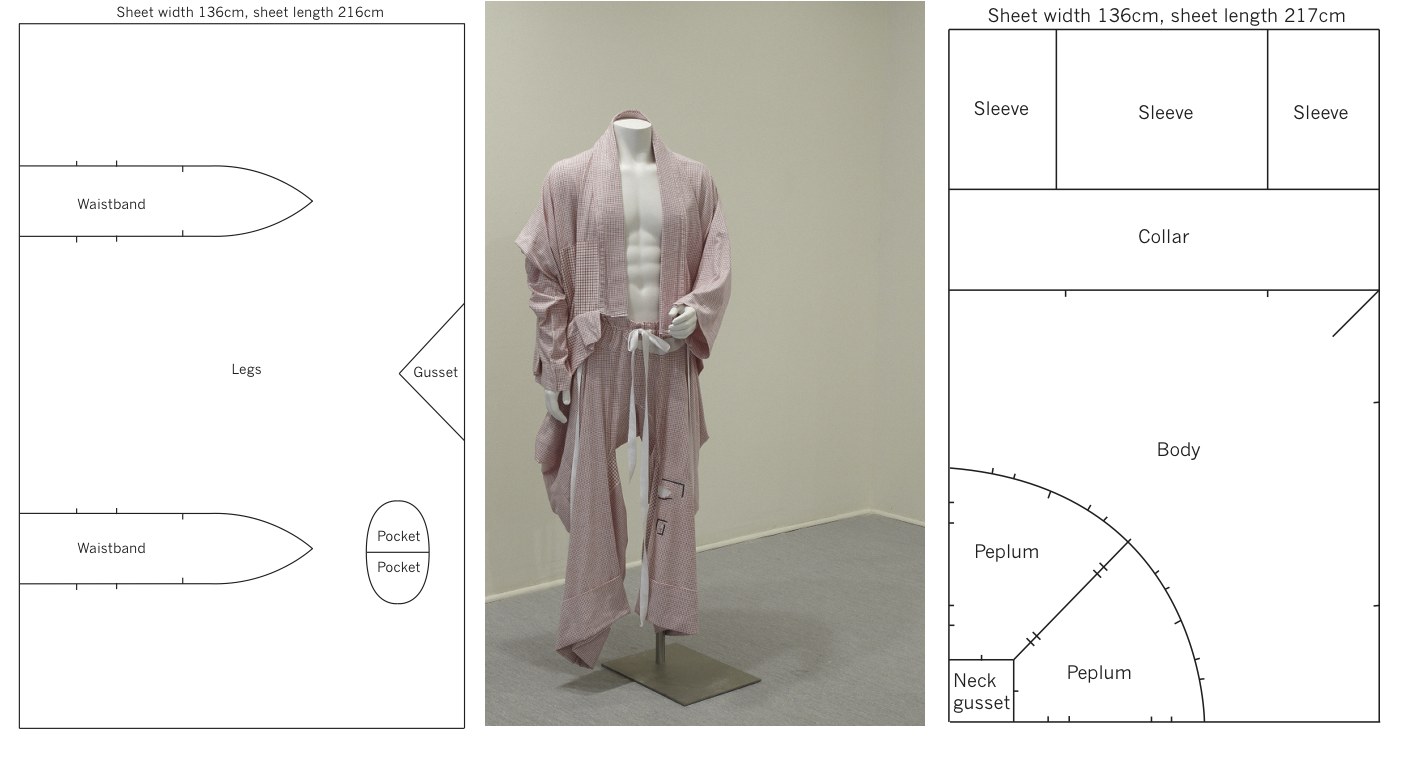

Endurance Shirt I, 2009

MC: How does the Zero Waste curriculum tie into these themes?

TR: I present Zero Waste within the larger context of fashion and sustainability and explain that it’s is one potential solution to this problem, but that there are of course other problems that have other solutions. The one thing that I really didn’t expect to come out of my research (it was kind of a nice side finding) is that Zero Waste fashion design can really be a gateway for other fashion design. You simply can’t design Zero Waste fashion in the same way that a lot of fashion is designed in the industry, where design is considered to be a sketch which is then given to a patternmaker. In Zero Waste fashion design, you have to begin making the pattern before you know how the garment is going to look. What that’s saying is that patternmaking is integral to the design process. That’s a shift in thinking and a challenge for a lot of people – both students and a lot of industry people that I’ve spoken with – because historically in fashion education, but also the way the industry is organized, all of those skills tend to exist within their own categories: you’ve got the designers, the patternmakers, the cutters, and the machinists, and there’s kind of a hierarchy. With Zero Waste, you have to bring the patternmaking and the cutting and the making into the design process. Once that shift happens, it actually becomes very easy.

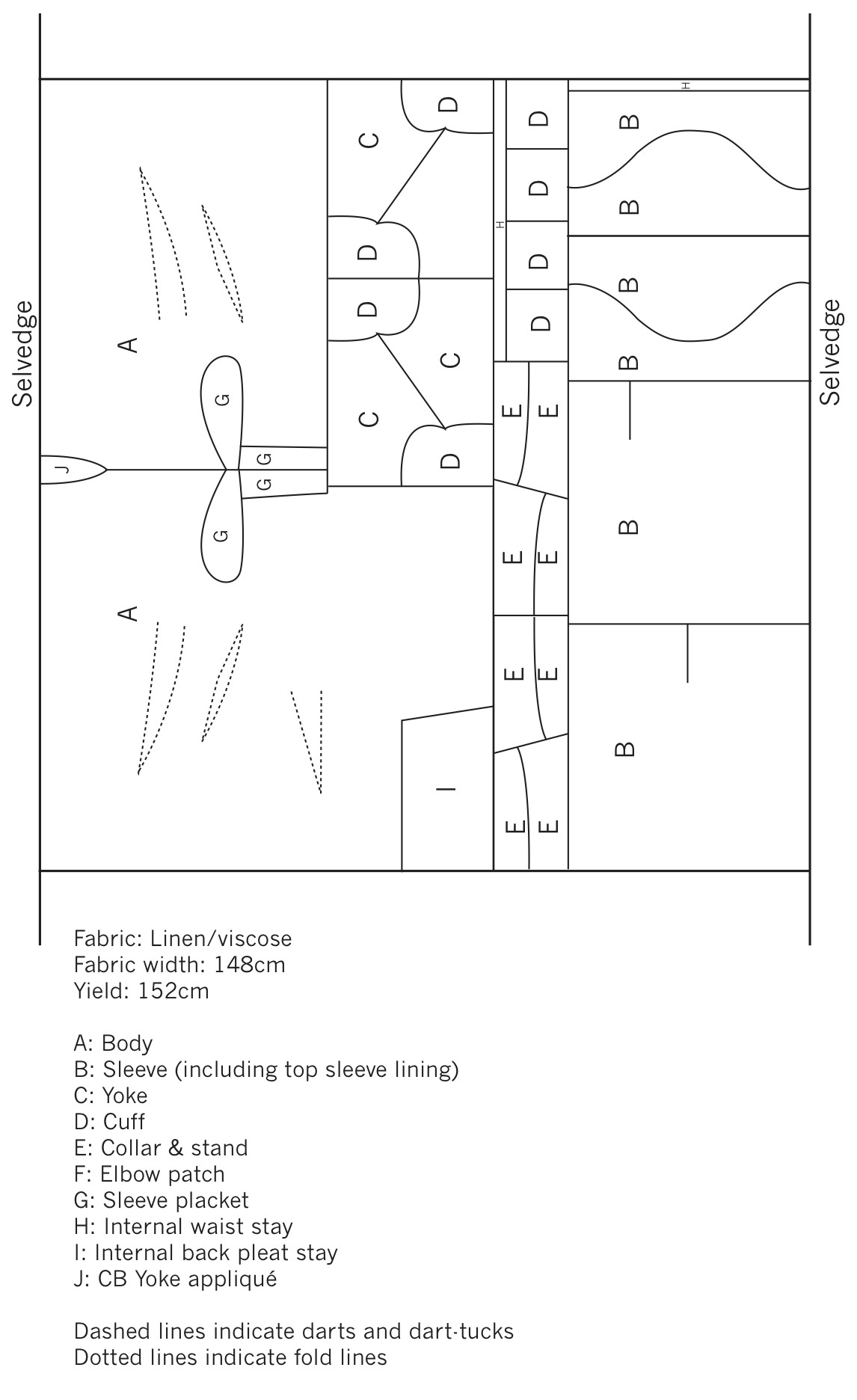

When I show students [examples of] Zero Waste pattern layouts, I always ask whether anyone is scared. Some of them always say 'yes' because they see these beautiful, finished Zero Waste pattern layouts. To some of them, these look like a form of witchcraft or black magic. But that’s just the final product. The process of getting there can be quite messy. That’s probably the one thing that’s shifted in my teaching: I make sure that I show the messy parts of the process, this combination of sketching, patternmaking, paper-folding, draping. Quite often I can’t say that ‘I designed that garment through draping’ because there were all these other messy parts to it. So I share that with students, but I don’t expect them to work like me. Every designer works differently. It’s dangerous to paint a picture of fashion design as one formulaic process.

Endurance Shirt I (Pattern), 2009

MC: Can you describe how sustainability integrates itself in the classroom setting, within the curriculum, even within the student dynamic?

TR: With my class of seniors, a lot of [the curriculum] has to do with asking questions and figuring out their place in the world as designers and as human beings. I’ve had students say ‘Why would I design anything ever, the world doesn’t need any more clothes.’ To me, that’s the most beautiful thing a student can say. Of course to complete their degree, they’ll have to produce their ‘six looks,’ but it’s a beautiful question to be faced with, because you only have to go shopping for half an hour to know that there’s too way too much stuff in the world.

Whether you worry about fabric waste or animal rights – whatever it might be – all of those things have to do with personal ethics. And that goes back to my teaching. I don’t impose any of those things on my students. What my job really is, is to give students the best possible information and a variety of viewpoints.

MC: You mentioned that research is really important for fashion designers. Could you explain?

TR: What I would really love to see is more questions asked about fashion design practice itself. Historically, I think that a lot of what we – fashion designers – thought about fashion design was based on assumptions. But it’s shifting. Every year there’s more fashion designers doing either Masters or Doctorate degrees, and that’s great. It’s not about academizing fashion design. It’s really about learning more about what we actually do and how it can be done in the future.

Timo Rissanan is Assistant Professor of Design and Sustainability at Parsons The New School for Design. He previously taught fashion design in Australia for seven years.

Mae Colburn is an independent textile researcher based in New York City.