On the Beauty of the Already Known: A Review of the 'Rik Wouters & The Private Utopia' Exhibition at MoMu Antwerp Fashion Museum

/by Roberto Filippello

In the face of current accelerationist tendencies in political and social theory pointing toward an intensification and repurposing of capitalism, the exhibition "Rik Wouters & The Private Utopia," on view at MoMu Fashion Museum Antwerp until February 26th, auspicates the return to a slow temporality that allows for the exploration of intimate connections with oneself and with others, suspending the pervasive mediation of the virtual into our everyday lives.

The exhibition commemorates the 100th anniversary of Rik Wouters's death. This Belgian fauvist painter (1882-1916) devoted a large part of his oeuvre to the exploration of serene and intimate domesticity through portraits of his wife Nel. His longing for a bucolic way of life, detached from urban frenzy, was informed by David Thoreau's transcendentalist inquiry into simple living as a conduit for personal introspection, and took artistic form in a series of unfinished canvases depicting scenes of harmonious homeliness.

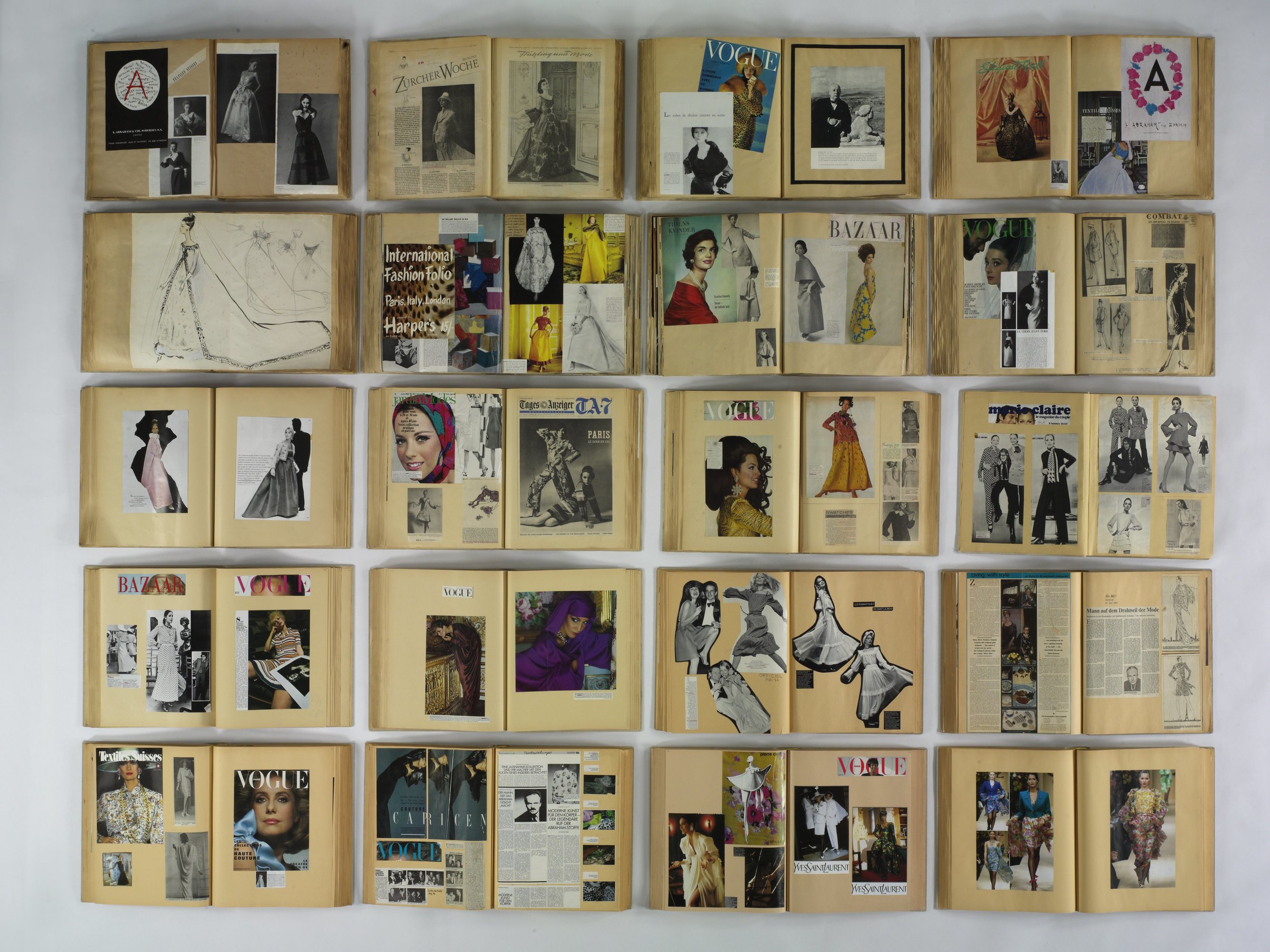

The exhibition, thanks to a multi-disciplinary curatorial philosophy, combines different media to dissect ideas, phenomena and aesthetics. Paintings and sculptures by Rik Wouters are displayed alongside ceramics, interiors and clothing by a number of Antwerp contemporary artists (BLESS, Atelier E.B., Berlinde de Bruyckere, Ben Sledsens) and fashion designers (A.F. Vandevorst, Ann Demeulemeester, Veronique Branquinho, Haider Ackermann, Bernhard Willhelm, Walter Van Beirendonck, Christian Wijnants, Dries Van Noten, Jan-Jan Van Essche, Martin Margiela, Marina Yee, Bruno Pieters, Anne Kurris) who have each in their own way addressed the desire to regain the secure intimacy of domestic life. Unfolding through seventeen thematic sections, such as 'Indoors,' 'Looking Outside,' 'Sculptures and Ceramics,' and 'Handicrafts,' the exhibition traces a visual narrative of how simple living has been translated into figurative and applied arts by artists and designers seeking shelter in an intimate creative environment, away from the turmoil of contemporary urban societies.

A renewed interest in artisanal techniques such as weaving, ceramics, and dyeing, as well as the usage of materials found in nature, are the key principles of the so-called "slow movement" to which this exhibit gives voice. As a reaction to the industrialization of fashion and its often unbearable hectic pace, the designers featured hereby make objects that are imbued with affective potential insofar as they result from a pondered and lived-through handcrafting practice. Their personal corporeal interaction with the matter reflects a utopian longing for an authentic way of being, living, and doing in the world. Antwerp-based fashion designer Christian Wijnants, for instance, dyes wool by hand and assembles collages of fabric using various application techniques such as knitting, embroidery and crochet. This hints at a bodily doing that disentangles fashion-making from the maze of corporate regulation and outsourced production to focus on the intimacy of affective engagement with fabrics and textures.

Reframing one's life in Thoreau's woods or in Thomas More's fictional island society, however, is not the only way to materialize utopic living. Throughout the exhibition, utopia comes to coincide with the beauty of the already known, figured through the making of Dirk Van Saene's home crafts, Bernhard Willhelm's crocheted accessories, or through the night silk gowns of A.F. Vandevorst, Ann Demeulemeester and Haider Ackerman. In a sensationalist era where technologies set out to design posthuman bodies, the familiarity with domestic attire conjures a sense of safety and tranquillity freed from the obsession with aesthetic futurism. According to Roland Barthes, the mark of the utopian is the quotidian (Sade, Fourier, Loyola).

It is this kind of utopia that the exhibition ends up exploring: rather than advocating the 19th century idealist project of going back to nature, which was indeed dear to Rik Wouters, who moved to the edge of the Sonian Forest to live together with like-minded utopian artists. The exhibit seems to embody the concrete possibility of finding beauty and joy in the domestic setting. Utopia, as an affective structure, can be materialized through the regaining of what we already know in order to propel its yet undisclosed potentiality into the future. It consists of living with pragmatic and optimistic imagination: using the past, or the pre-existent, to act presently at the service of a better future.

Marina Yee, a member of the historically renowned fashion collective 'Antwerp Six,' which laid the foundation for current Belgian fashion culture, began to turn away from fashion's cyclical consumption in the 1980s and since then has worked at her own pace, focusing on sustainability and artistic development. In the exhibit, an oil painted replica of a 19th century camisole and a sculpture made of glass, silver, copper, wire and leather by Yee are on display. Bruno Pieters, with his collective ethical label 'Honest by Bruno Pieters' questions the norms and regulations enacted by mainstream fashion by sharing with the customer how the garments are manufactured, the hours required for their completion and the pay received by the seamstresses. These details constitute the core of his utopia for a sustainable future.

These designers share a creative practice grounded in the ambition to redesign clothes, interiors and all the objects of the everyday life beyond the unethical limitations posed by industrialization, imagining a future in which applied arts contribute to human and environmental well-being. Such a perspective is invested with the optimism of finding beauty in the creative process and of letting the consumer participate in it: while acceleration has failed to produce a collective sense of accomplishment, slow movement and sustainability foster a sense of belonging in which harmony may be intimately felt and shared.

Roberto Filippello is a fashion editor and writer whose academic expertise lies at the intersection of fashion studies and queer theory. He is an alumnus of the Master of Arts in Fashion Studies at Parsons The New School, where he has taught courses on the history of fashion and critical analysis of fashion photography. His current research focuses on the articulation of queer affectivity in fashion and pornography.