by Ana Carolina Minozzo.

Satin Wrap Band Snood by Maysaa

Satin Wrap Band Snood by Maysaa

Earlier this summer, a crucial step in the innovative research in the field of fashion studies took place in London. A one day symposium ‘Mediating Modesty: Fashioning Faithful Bodies’ presented the conclusions and opened a space for discussion after a year of studies conducted by the ‘Modest Dressing: Faith Based Fashion and Internet Retail,’ a research project, which operates as a platform of multidisciplinary intellectual interchange on the topic of modest dressing.

Professor Reina Lewis, from the London College of Fashion, has been conducting ongoing research on gender, ethnicity and orientalism. During her investigations, she came across issues relating to Western, especially European, attitude towards Muslim women. “They dress differently, they cover their bodies differently and that is seen as a controversial political symbol by Western and European society...and rarely as a fashion statement, although they adorn themselves and consume fashions as much as any other group” comments Professor Lewis.

According to Lewis, religious women, especially young Muslim women, are also consuming fashion, and their consuming behavior has changed in relation to the internet. Those girls are also part of the religious revivalism movement that we witness at present, which generates specific social impact that is worth analyzing. ‘I became interested in expanding these questions I encountered to Christian and Jewish communities. They also share this juxtaposition of ways of dressing in contrast with the secular world’, adds Lewis.

She was then joined by Dr Emma Tarlo, from Goldsmiths College and the researcher Jane Cameron and, in February of 2010, the idea had a shape and a name. She explains: ‘We wanted to look at the internet for it being a space of crossing boundaries of faith and territory. It is a deterritorialised and dematerialised sphere, which offers the possibility for a new type of dynamics’. In her own words, the internet ‘allows to torn apart the binary divide between the religious and the secular worlds’, and this perspective guided the variety of points studied and analyzed through the last year, which were discussed during the symposium at the London College of Fashion.

This month, the papers presented during the event as well as a podcast with the complete coverage of what was talked about became available online, on the page of the Religion & Society organization. You can download all this information here.

You can also find a brief summary of the symposium below, with an introduction to the work of each of the invited readers from England, Europe and the US.

Teenage Girls in London, Photo by Ana Carolina Minozzo

Teenage Girls in London, Photo by Ana Carolina Minozzo

The day began with Professor Frances Corner, the Head of College at LCF, welcoming the participants and stressing the relevance of addressing the concept of ‘sustainability’ in Fashion. Social sustainability must also be in our agenda, by which we should consider diversity and inclusion, the consumer sustainability. At that very moment, the relevance of what was about to come was set and from then on, a rich and energetic exchange took place.

Professor Reina Lewis was the first to share her findings with the audience. She drew on the internet’s capacity of presenting fashion solutions, challenging spacial and cultural constrictions and permitting a dialogue between women from different communities and religions. This ‘deterritorialized’ platform of discussion that are blogs and general websites of e-tailing are sometimes informed by a religious spiritual mission. Such arguments add to the seeming contradiction found in the relation of modesty, beauty and fashion. The last carrying with it the necessity of being ‘the first’, ‘the most’ as well as ideas of exclusivity and competition.

However contradictory certain websites and forums may seem, their cultural impact is remarkable. Through the cross-faith online debate, a fragmentation of the religious authorities is noticed, as well as changes in the religious discourse itself. A challenge of the male authority, in some cases, is also present, by means of the new access to power given to women through such virtual platforms.

Issues surrounding Muslim modesty dressing, specifically, were further explored by Annelies Moors, from Amsterdam University. She stressed that modest dressing is also considered a religious practice in itself, a form of worship which allows a social connection with ‘equals’ united in faith. In the case of Islam, dress codes are related to its public evaluation, especially when Islam is a minority group, and it had a strong and meaningful role through different moments in history. Moors also questioned the concepts of ‘modesty’ in different communities, which vary from humbleness, chastity, and purity to not resembling a man. Techniques used to produce this particular identity, of the modest self, were discussed alongside the greater question of how god and the community influence one’s ability to make choices.

The Muslim modesty debate was then discussed together with Jewish modesty and the online encounters of these two faiths was the subject of Emma Tarlo’s research. Parting from the idea of segregation and differentiation inherent to a faith-based dress code, the actual concern of women to buy only from shops or brands, which correspond, to their religious group was questioned. By means of a through analysis of the online inter-faith dialogue, Tarlo recognized certain recurrent topics of discussion such as: the value of modesty as a female attribute; gender differentation; sex only within marriage and the idea of attractiveness versus the ‘sexiness’ of fashions.

Transporting the audience to the US, the day’s conversation was joined by Barbara Carrel, from the City University of New York, who focused on New York based community of Hassidic women in her research. This very interesting group of women have strong shopping habits and, although their outfits may look like they are ‘all the same’ to outsiders, a rich variety of embellishments can be found in the way they adorn themselves. The Bobover women were carefully studied by Carrel, who managed to analyze their dress code in contrast with secular fashion and also on contrast with other orthodox Jewish groups. The modest dressing regulations, in this case, contribute not only aesthetically to the formation of a group identity, but also mark a form of protection towards the ‘dangers’ of a secular society which lives by a distinct ethos. A negotiation of fashion, taste, tradition and faith is constant in the life of a Bobover woman, who will chose to adapt (or not) certain mass produced garments and reestablish the rules of dressing in faith.

A round up of online forums and an analysis of what sort of questions and interaction is being presented within their scope was read by the researcher Jane Cameron. As an online ethnographer, she spotted recurrent themes in order to clarify the motivations behind dressing modestly. Supported by the anonymity of the internet, women from all sorts of religious and non-religious backgrounds discuss the ‘level’ of modesty of certain garments, swap tips on how to cover yourself or how to be an example to your children whilst exchanging judgment over the most varied current issues which relate to modesty, in general."

Last but not least, Daniel Miller, from UCL, came into de debate to share facts of his ongoing research on denim and connect it with the event’s theme of modesty. Undressing - if this term is allowed here- the semiotic and cultural aspects of denim through history and across the globe, the orthodox Jewish prohibition of the material was explored. For its property of blurring, if not eliminating completely, distinction of class/gender/age and so on, the fabric is seen as a threat to a community that thrives on maintaining itself distinguished from secular people and other group not just in faith, but symbolically as well.

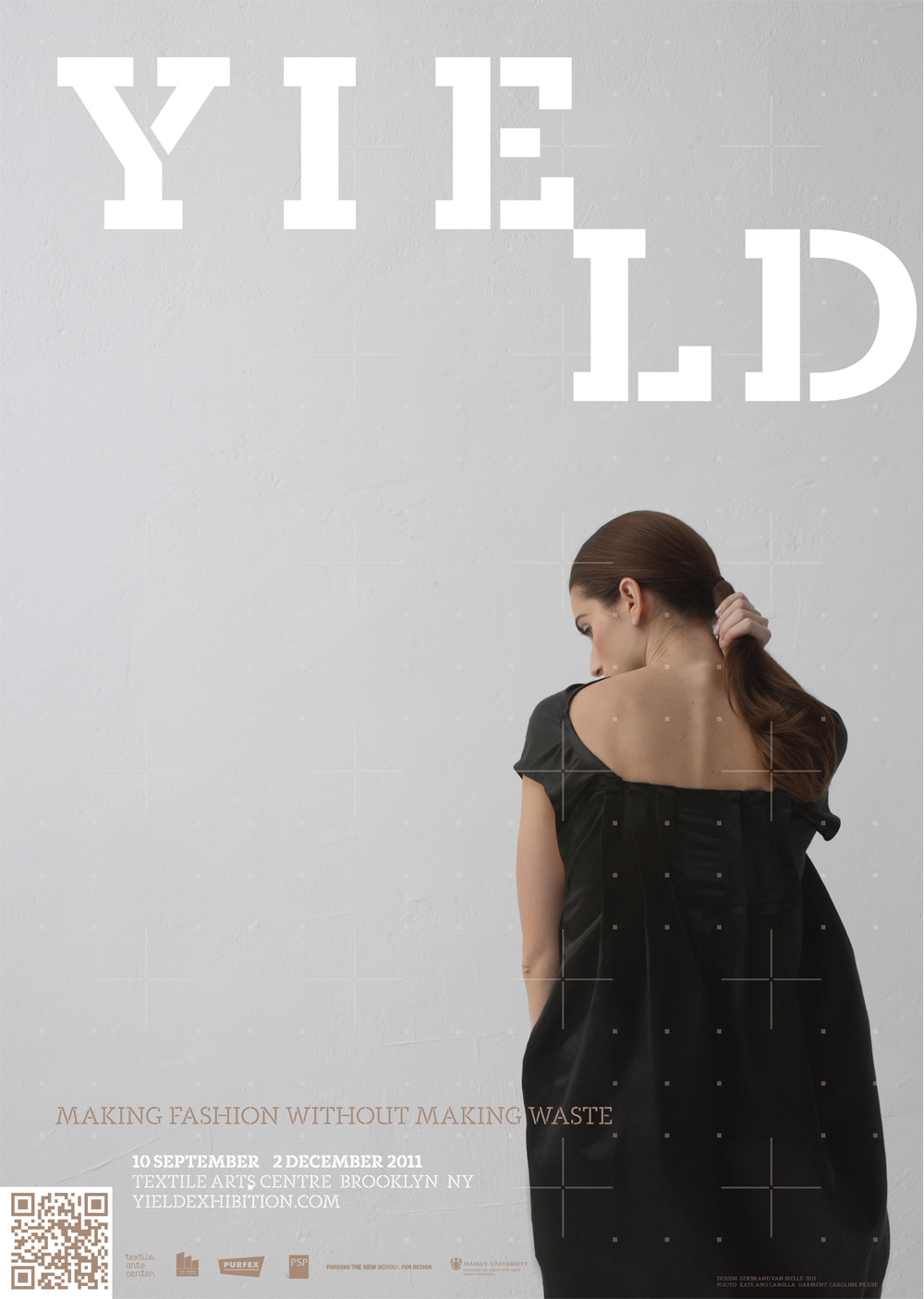

At the very end, we were joined by designers Shellie Slade and Hana Tajima-Simpson founders of Mod Bod and Maysaa UK respectively, in an interesting juxtaposition of academics & their ‘object’ of study. The public had the opportunity to listen to and ask questions to both of the very successful modest fashion professionals, who rose with the internet and still use it as a main platform to express their ideas of faith and creativity.

The discussion, surely, did not come to an end with the closure of the event. Quite the opposite, Mediating Modesty opened the doors of reflection and enticed further debating and thinking over this important contemporary phenomenon.

Ana Carolina Minozzo is a Brazilian-born and London based writer and fashion researcher.

She is finishing her BA at the London College of Fashion whilst working as a journalist and working on her first novel.

"Before Minus Now," Spring/Summer 2000

"Before Minus Now," Spring/Summer 2000