Fashion and Design at the Victoria & Albert

/

Pavonia, by Frederic, Lord Leighton, 1858-59, © Private Collection c/o Christie's

by Laura McLaws Helms

Currently on view at the Victoria & Albert museum in London are two exhibitions that deal with highly refined design, from a century apart. “The Cult of Beauty” (on view until July 17th) looks at the Aesthetic movement that sprouted from the members of Pre-Raphaeliteism in England in the 1860s. Concerned with “art for art’s sake,” the movement reached its apogee in the 1880s and 90s when it moved from strictly the province of artists to the passion of aristocrats and then into the mainstream. While it arose from the fine arts, Aestheticism was concerned with beautiful design in all aspects of life resulting in a broad range of Aesthetic design that is covered in this large exhibition. Sequenced chronologically, the curator, Stephen Calloway, deftly intermixes paintings, sculpture, furniture and more in rooms painted in such Aesthetic tones as peacock and ‘artistic’ green.

A small section devoted to Aesthetic dress showcases their desire to reject “the corsetry, uniformity and commercialism of high fashion” while encouraging “individuality” and drapery. Notably different than the upholstered, bustled dresses prevalent at the time, on view is a “late Medieval” sage green velvet dress from Liberty’s Artistic and Historic Costumes Studio. A return to the ideals of the Middle Ages, when craftsmanship was seen to be celebrated, was one of the main tenants of Aesthetic design and its influence is present in costume in the loose, draped gowns and flattened nature motifs. Men’s aesthetic dress is irrevocably associated with Oscar Wilde’s velvet knickerbocker suit, of which a variation is on display. Other garments and accessories, including a smoking cap, reflect the drawing of inspiration from the East. Though the selection of dress in the exhibition is limited, for the lover of fashion the whole show is a glorious paean to all that is beautiful, making for an irresistibly enjoyable experience.

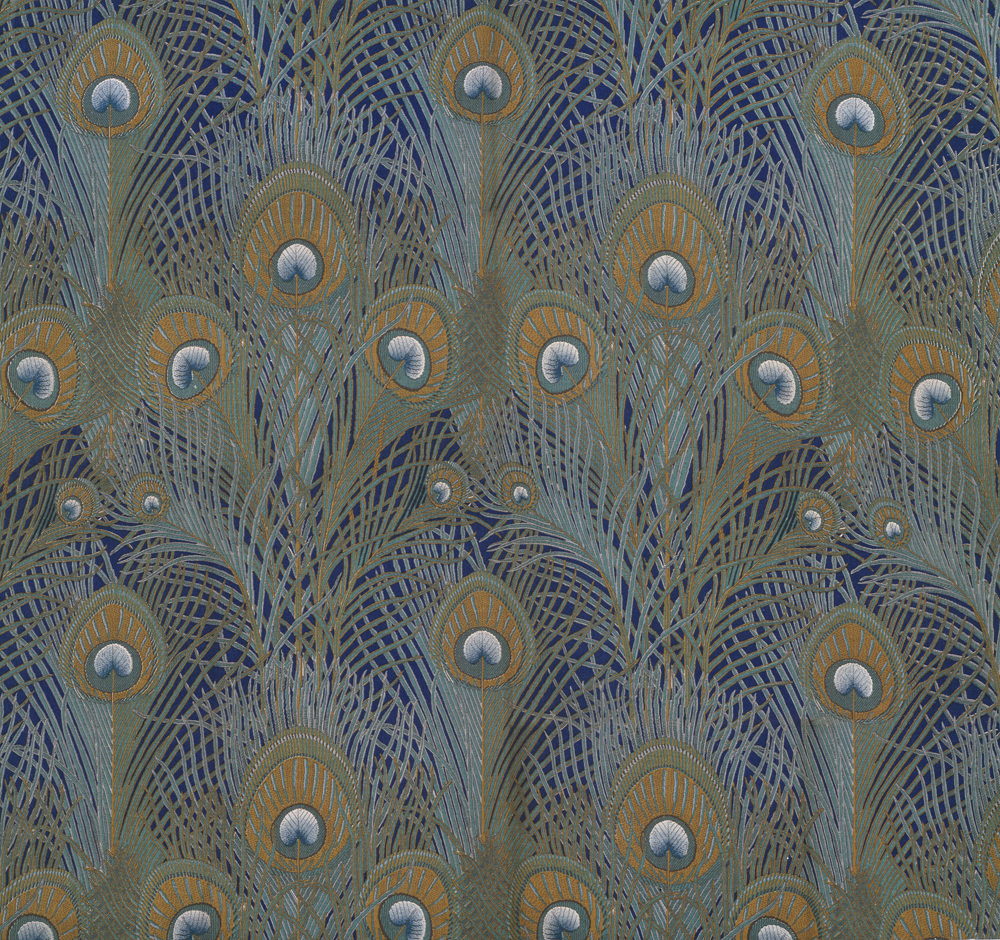

"Peacock Feathers" furnishing fabric, by Arthur Silver for Liberty & Co., 1887, © V&A Images

A total contrast, nearby is the main exhibition space for “Yohji Yamamato” (on view until July 10th), a bright hall with scaffolding erected down one side. The central area holds over sixty of his designs, mainly from the 1990s and 2000s, while on the wall behind the scaffold is a multi-media timeline charting his forty years in design. The mannequins are arranged in small groups, standing at eye level with no barriers between the viewers and them. This allows for almost unprecedented access to garments in a fashion exhibition — inviting the museumgoer to walk around the mannequin, come up close to analyze fabric and manufacture, do everything but touch. Ligaya Salazar, the curator, visited the Yamamoto archives, choosing a selection of women’s and men’s pieces that reflect his individual vision, combining an Asian belief in the primacy of the cloth — the exhibition begins with Yamamoto’s quote of how “fabric is everything” — with a deep interest in the work of Western couturiers.

Yohji Yamamoto exhibition at the V&A, 2011

Dotted around the museum are site-specific installations of some of his pieces, determined to reflect aspects of “Yohji Yamamoto’s design world.” Situated in amongst works of art and historical rooms, his designs take on new meaning in their new environments — red wool dresses and coats shown with fifteenth century tapestries blend with the era yet also emerge as completely modern and alien to the tapestries. While the use of installations spread out amongst the museum creates a certain engagement with the viewer, a similar interaction between varied museum space and Yamamoto’s garments was already done in the three-part retrospective of his work, “Triptych,” held in 2005 and 2006 at Galleria d’Arte Moderno of Palazzo Pitti in Florence, the Musee de la Mode et du Textile in Paris and the MoMu in Antwerp. The exhibition also fails to provide any information on Yamamoto’s work processes — though the expertly and innovatively cut pieces might be thought to speak for themselves, a greater depth of information would be appreciated. It is clear from the blog Ligaya Salazar maintained during the process of curating this exhibition that she learned a great deal of knowledge about Yamamoto and his work, which would have made a welcome addition to the two didactics included and would have helped to impart a more complete understanding of the Japanese enigma.

Yohji Yamamoto, Satellite display at the Tapestry Gallery, V&A, 2011