A Review of "Silks and Prints from the Abraham Archive – Couture in Colour" at MOMU

/by Philip Warkander

Hubert de Givenchy, Winter 1971/72. Photo: Gian Paolo Barbieri. Gazar Brodé Chenille, Winter 1971/72. Silk and entamine, shantung appliqué. Abraham Archive.

Hubert de Givenchy, Winter 1971/72. Photo: Gian Paolo Barbieri. Gazar Brodé Chenille, Winter 1971/72. Silk and entamine, shantung appliqué. Abraham Archive.

In1982, sociologist Howard S. Becker published the book Art Worlds, in which he argued that art is not the production of single individuals – artists – but rather the result of a number of interactions among people and materials, together constituting the contexts in which art works can be defined as such. According to Becker, art is not the result of one person’s work, but is a value constructed according to specific settings, or art worlds. This perspective has become hugely influential in art theory while also having an impact in fashion studies, most notably through sociologist Yunyia Kawamura’s Fashion-ology: An introduction to Fashion Studies (2004). Explaining how fashion comes into being, Kawamura aligns herself with Becker by claiming that fashion should not be understood as the product of designers working in creative isolation in their studios, but instead as the effect of an entire system of interactions, based on the negotiations between designers, stylists, magazine editors, PR consultants, retailers as well as a number of other actors.

Currently on view at the Fashion Museum in Antwerp is an exhibition exploring the effects of this theoretical perspective on the textiles, prints and fabrics manufactured by the Swiss company Abraham Ltd. The exhibition was originally produced by the Swiss National Museum in Zurich, but the Antwerp version (in the museum’s own words) “recaptures and expands” the original version. Placing the materiality of the fabrics and the print designs at the center of the exhibition, the process of producing prints is explained in detail, not only making for a pedagogical but also for an aesthetically advanced display. For example, the exhibition shows how a rose pattern, which was one of the company’s trademark prints, required nine stencils to print nine colors in nine separate print runs. The fabrics produced by Abraham Ltd. were so intricate that they became – due to the high cost of production – often reserved for haute couture, thus establishing intimate interconnections between the Swiss company and French couture houses such as Dior, Balenciaga, Givenchy and Yves Saint Laurent. As a result, Abraham Ltd. became one of the key players in the high fashion industry of the twentieth century, their patterns and textiles shaping much of what is otherwise generally assumed to have been designed within the couture houses.

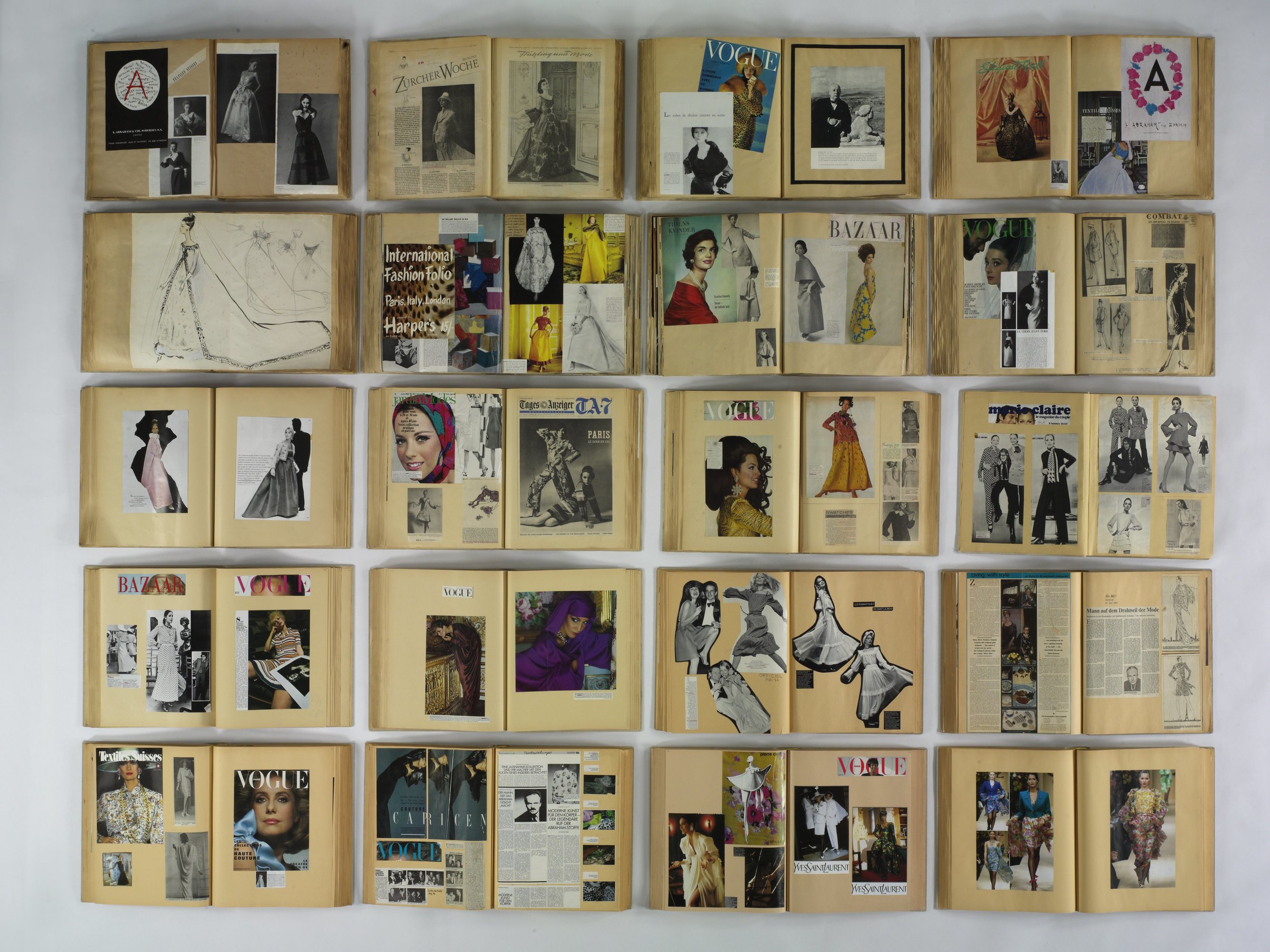

Installation with 20 Abraham scrapbooks, 2010. Abraham Archive

Installation with 20 Abraham scrapbooks, 2010. Abraham Archive

The textile supplier worked closely with Dior haute couture throughout the 1950s, and when Christian Dior passed away, the company’s leader Gustav Zumsteg met Yves Saint Laurent at his funeral, marking the beginning of a partnership that would hugely influence contemporary fashion, ending with Yves Saint Laurent’s last couture collection and the demise of Abraham Ltd, both in 2002.

Abraham’s technical possibilities for producing blow-up prints had a huge impact on the fashion of the 1960s, while the company’s talent for creating animal prints enhanced fashion’s “playwith abstraction and illusion”, as stated in the exhibition texts. Monochrome fabrics show the complexity of the materials, sheen surfaces and raw structures creating unexpected and organic patterns. The exhibition creates a narrative through a textile archive of the recent past, but with a new perspective on the creations of some of the most established and iconic designs. The works of Pierre Cardin, Nina Ricci and Pierre Balmain are exhibited here as products of collaborations, the result of successful partnerships between textile supplier and fashion house. These relationships are explored to their fullest in the small exhibition room named “Abraham Revisited”, in which five contemporary fashion designers (Akris, Peter Pilotto, Dries Van Noten, Heinrich Brambilla and Diane von Furstenberg) selected their favorite fabric and prints from the Abraham archive and then projected these onto mannequins wearing their own iconic designs. The result underlines the power of fabric and patterns, altering the appearance of the fashion designs with each new projection.

Focusing an exhibition on a fabric company unknown to most people outside of the fashion industry might sound like a niche strategy, targeted mainly on those already in-the-know However, the beauty of the materials is overwhelming and the story of this company fascinating, so much so that I was brought to tears as I walked through the exhibition space, in awe of the understated elegance and vivid display of craftsmanship. Also, the mapping of how the fabrics were once shipped to over forty countries (detailing quantities, dates, cities) worldwide chronicles the complexities of the system of high fashion while momentarily bringing back to life all the many individual but largely anonymous actors, without whom the iconic designs of the large couture houses would never have come into existence.

Philip Warkander recently completed his PhD in Fashion Studies, and is currently working as a freelance fashion writer and consultant, while also teaching fashion theory and gender studies in Stockholm.

Silk and Prints from the Abraham Archive. Couture in Colour. Photo: Boy Kortekaas

Silk and Prints from the Abraham Archive. Couture in Colour. Photo: Boy Kortekaas